...

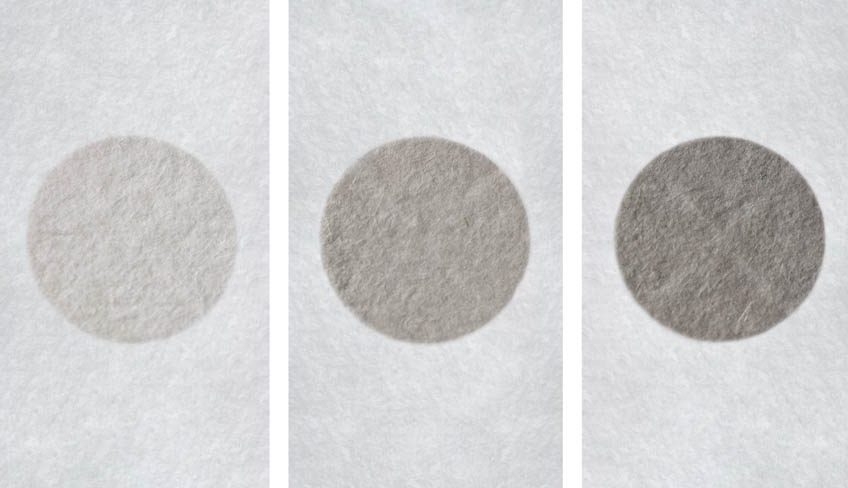

When it comes to public emergencies, be they due to a virus, pollution, or war, we must act together. This includes not only people from different nations but also animals from different species and forces, both living and non-living. Our increased attention to the air and what it carries inside itself foregrounds the issue of environmental racism with its numerous casualties and countless battlegrounds. The continuous sonic ensemble Songs for the Air, specially developed for the Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt, gives voice to particles floating in the air—among them the harmful substances of PM2.5 and PM10. According to the World Health Organization, 4.2 million deaths occur each year as a result of exposure to outdoor air pollution, with low- and middle-income countries experiencing the highest burden. As Achille Mbembe wrote, “the long reign of capitalism has constrained entire segments of the world population, entire races, to a difficult, panting breath and life of oppression.” In attunement to the bodies and forces that breathe together, Saraceno draws specific attention to inequalities of the air that are often unforgivingly site-specific.

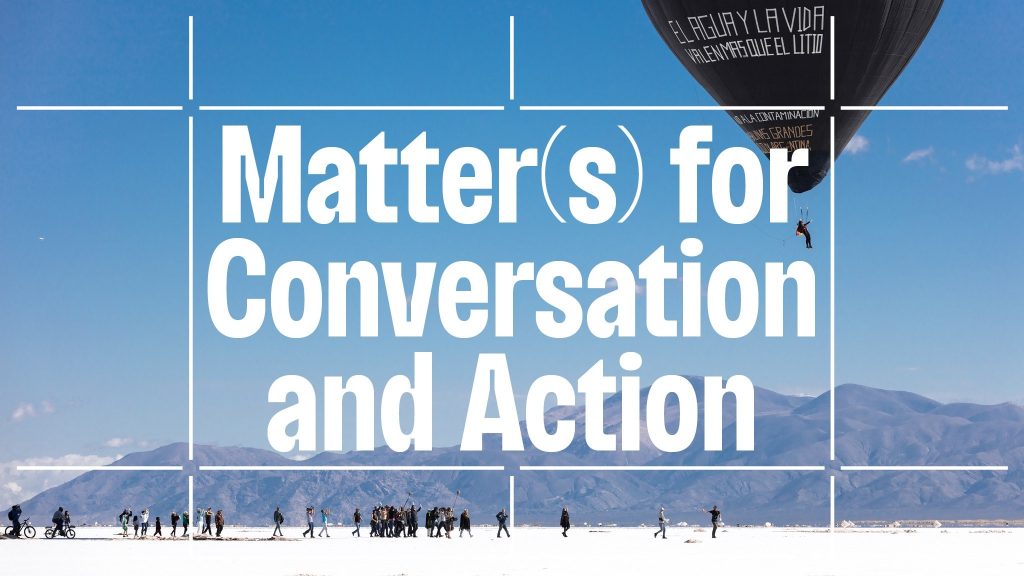

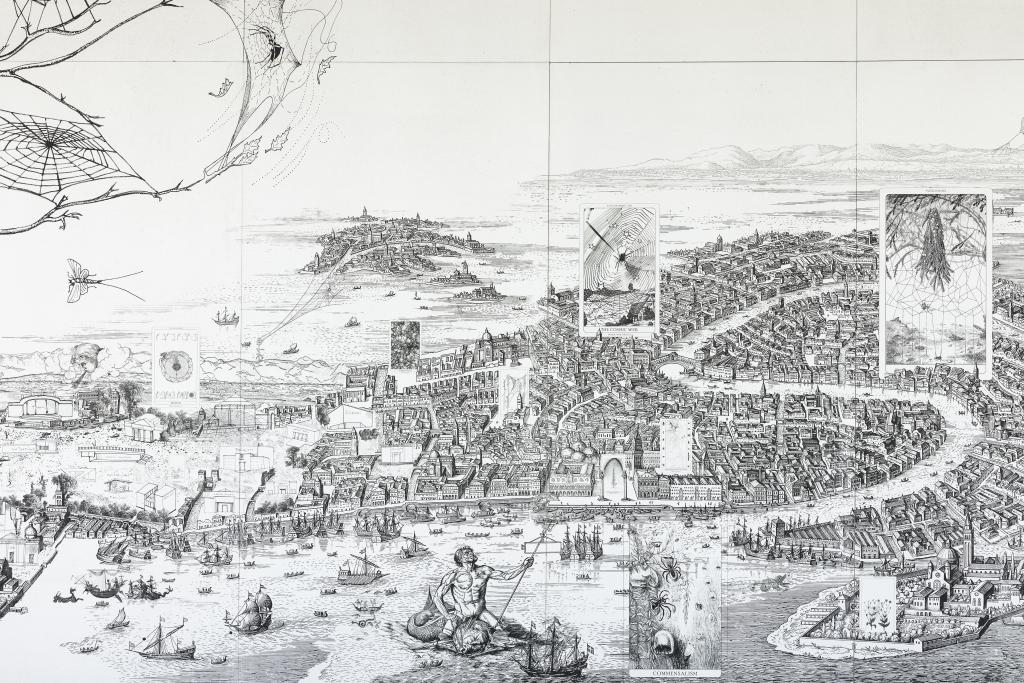

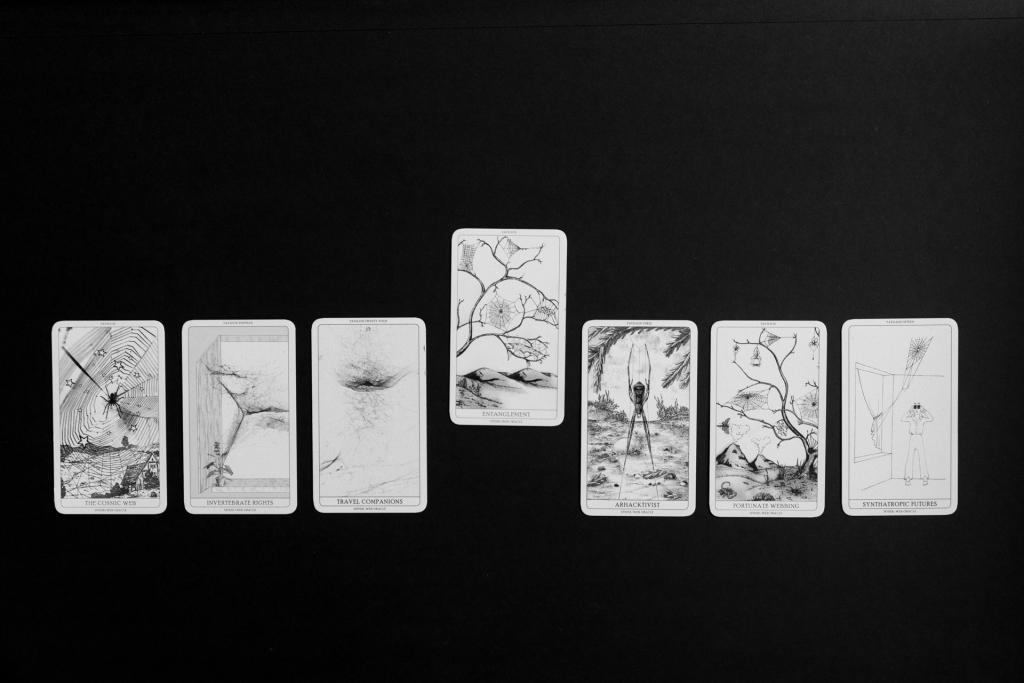

The exhibition made visible the many others, living and non-living, with which we share our planet. Through his work with the community groups Aerocene and Arachnophilia, Saraceno sees a future for all things—free from borders, free from fossil fuels, free from the extractive, colonialist and capitalist ambitions that divide us. Through a series of digital artworks, including Saraceno’s Arachnomancy and Aerocene apps, he challenges technology to connect us to the world, bringing the exhibition into your phone and home. Each App begins with the story of doing it together. “Right now”, he states, “we have our priorities backwards: capital flows freely, propelled by the fossil fuel economy, while people, empathy and cooperation are stopped at borders.” Saraceno reminds us that following the patterns and forces of the wind, the sun and weather: the air has no borders. It belongs to no one yet gives itself freely to all. He also draws attention to the massacre of insects worldwide, which make up part of the Sixth Mass Extinction due to the promulgation of glyphosate and other pesticides, the loss of habitat and unrelenting climate change.

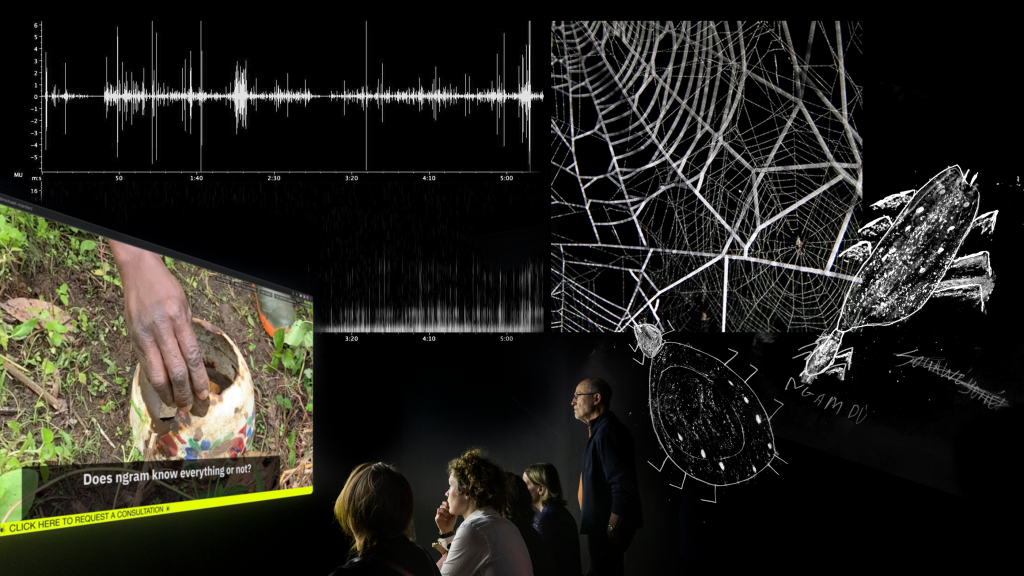

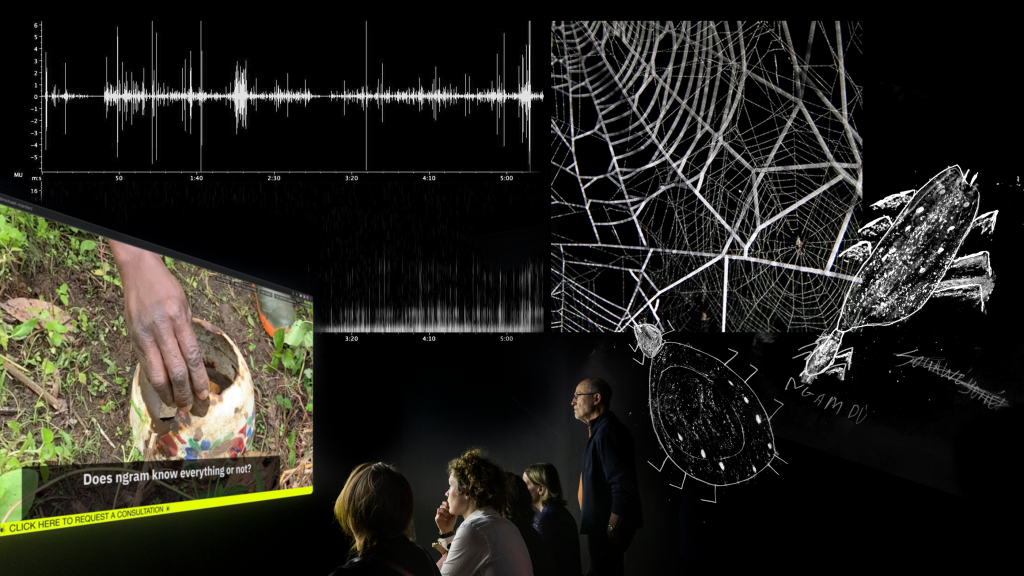

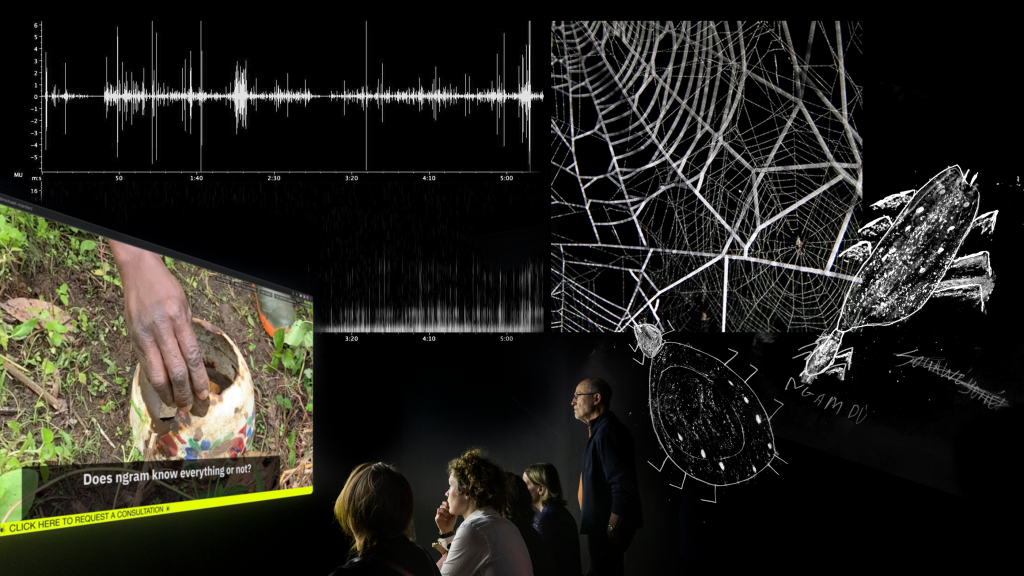

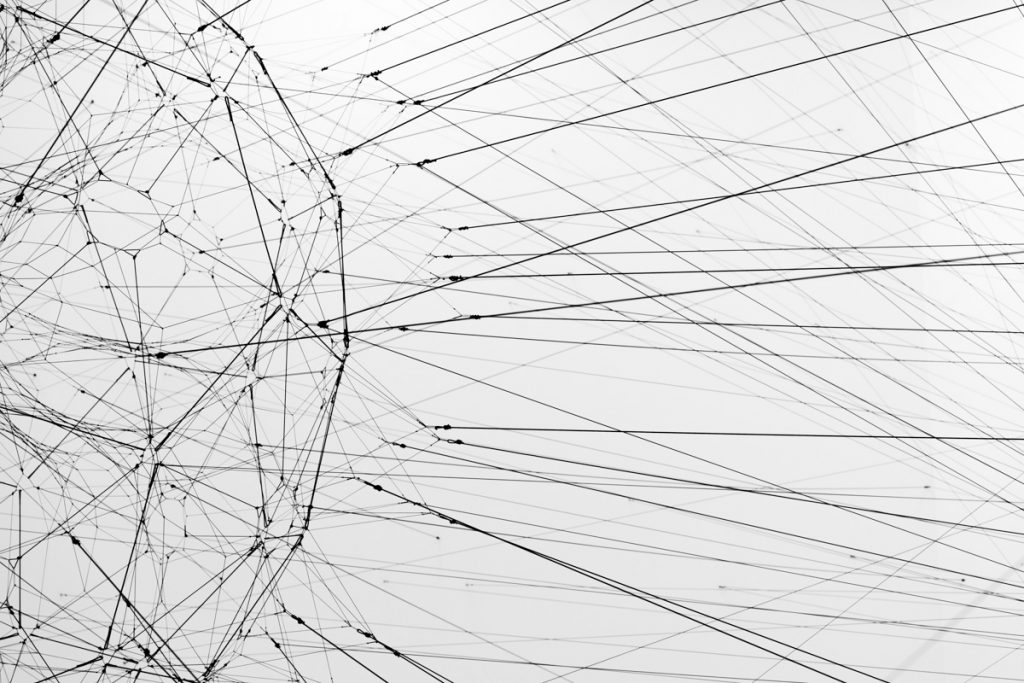

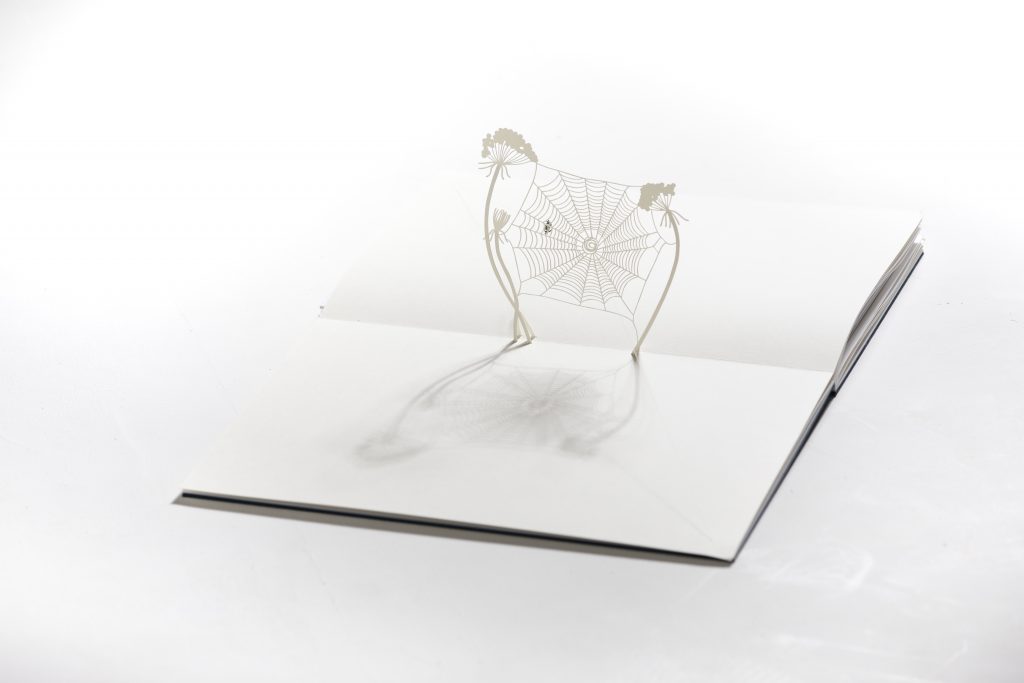

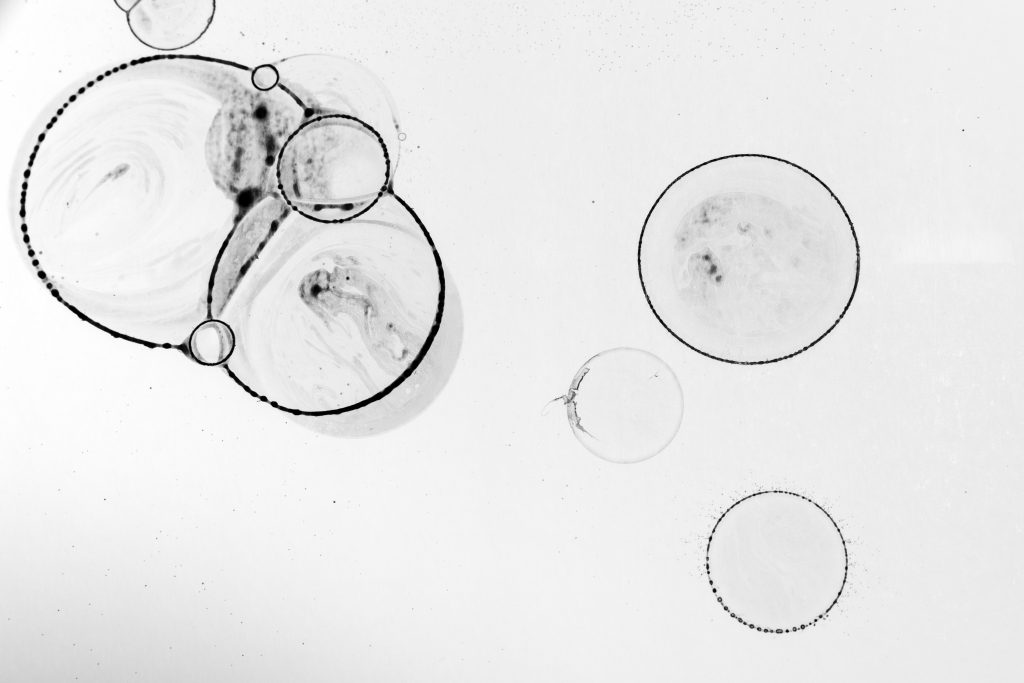

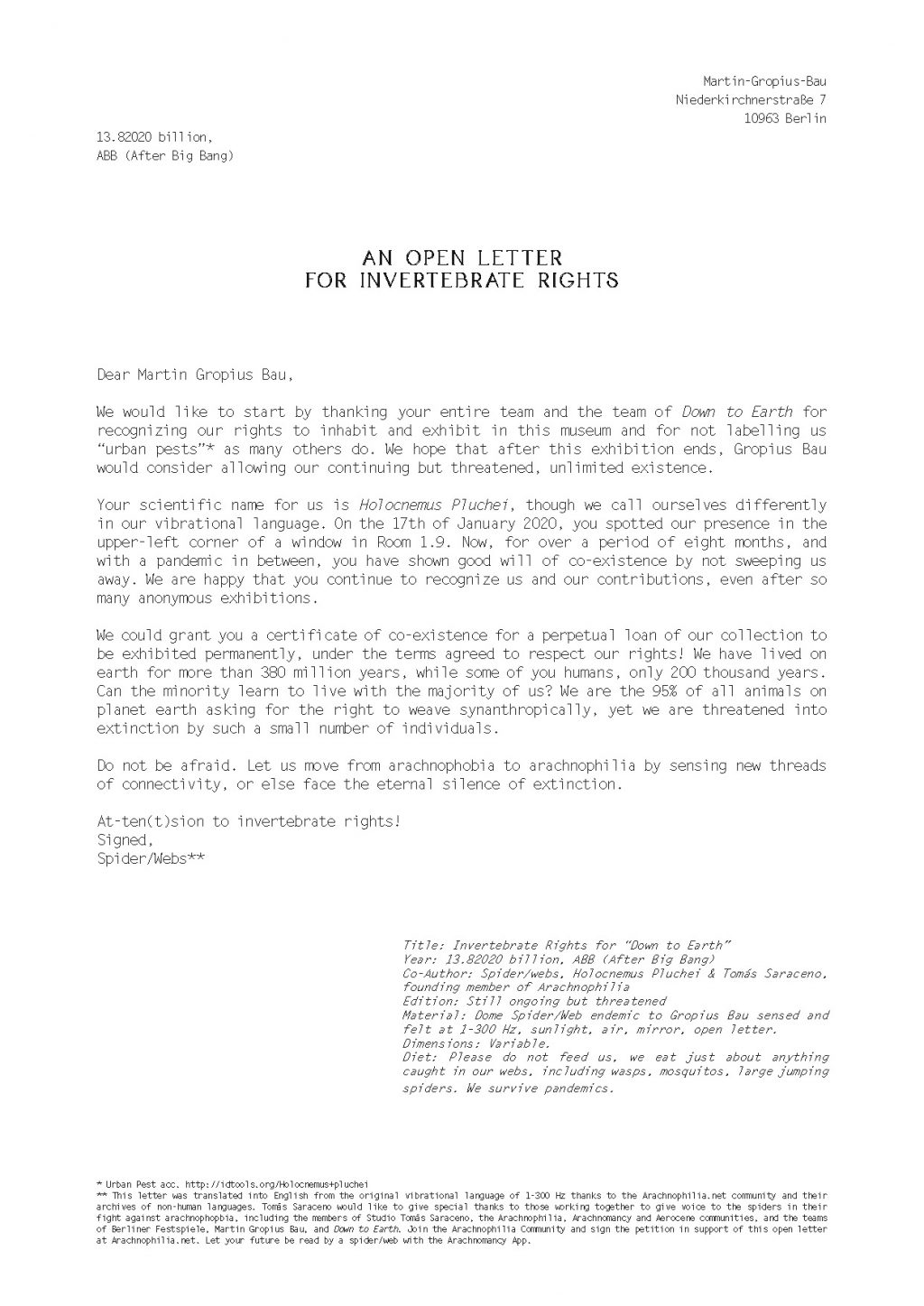

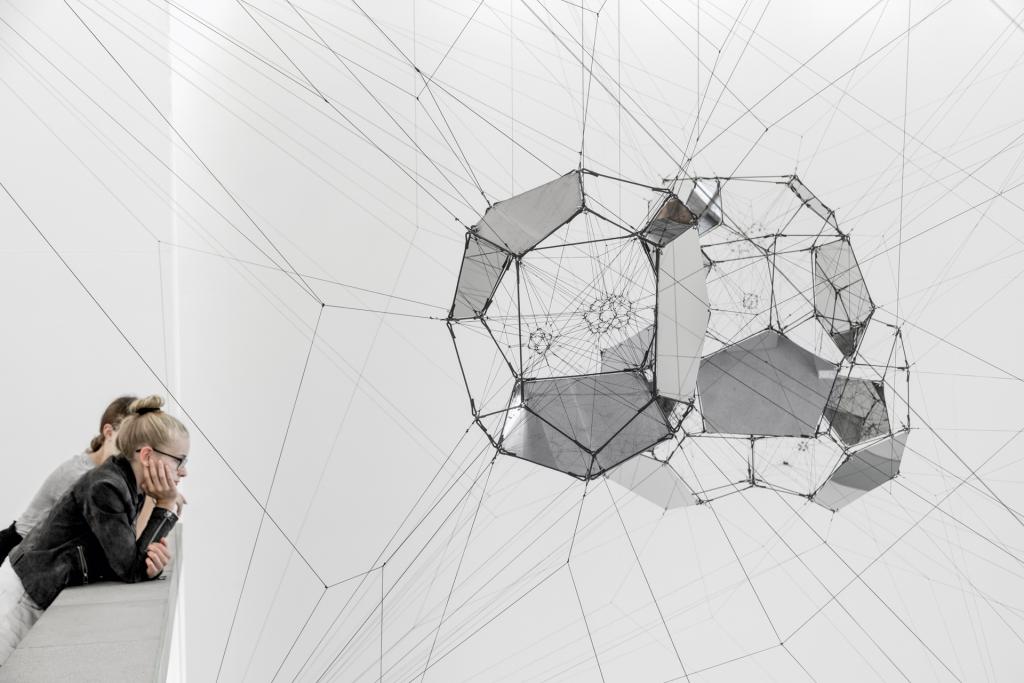

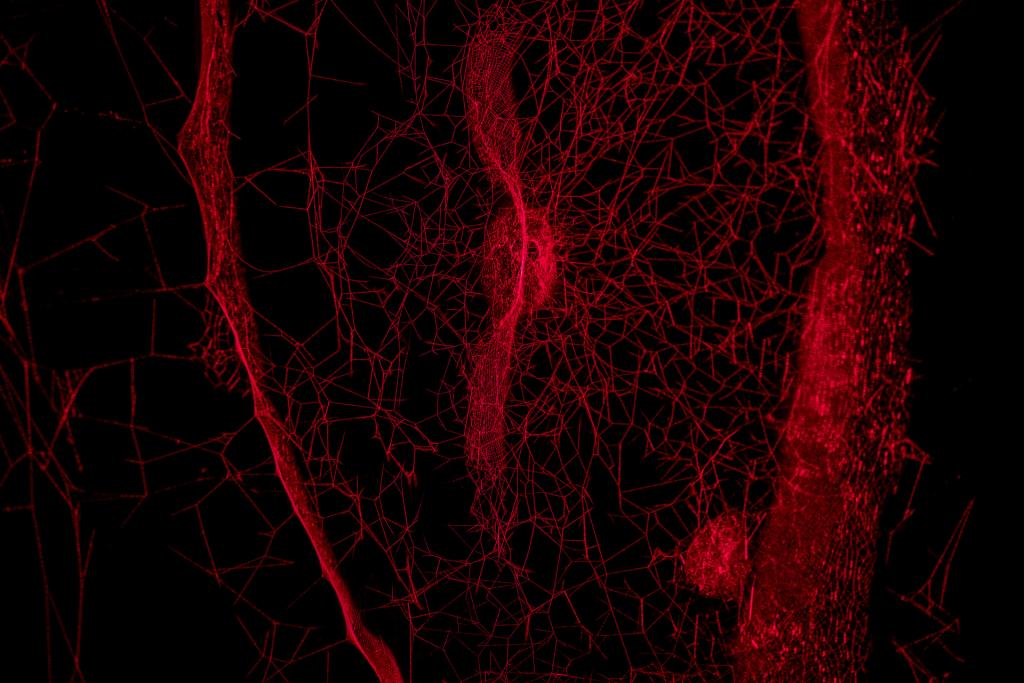

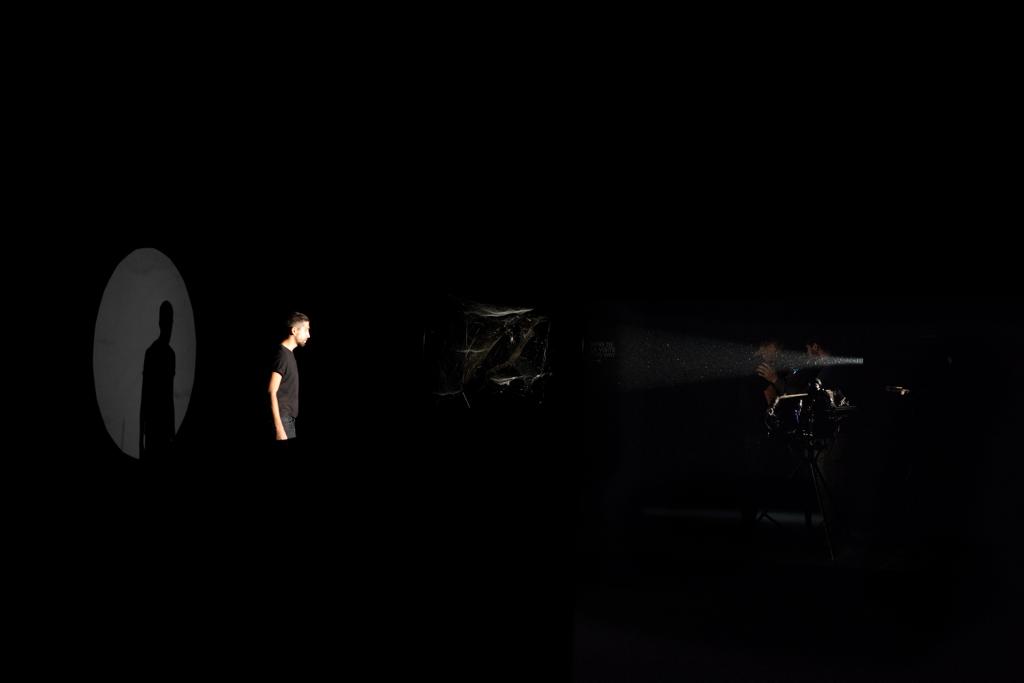

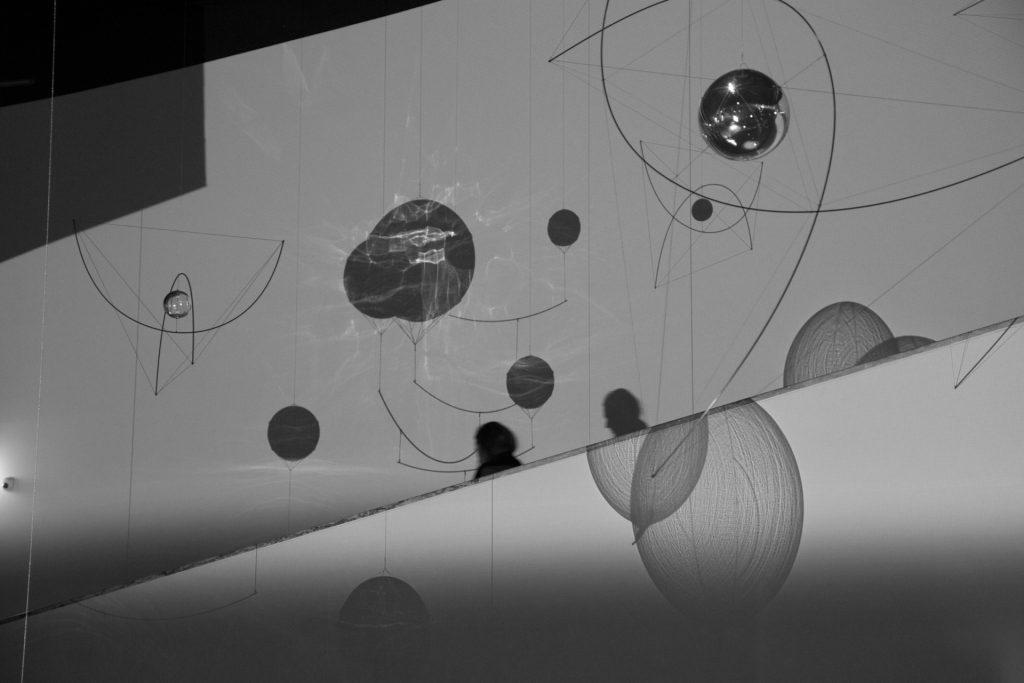

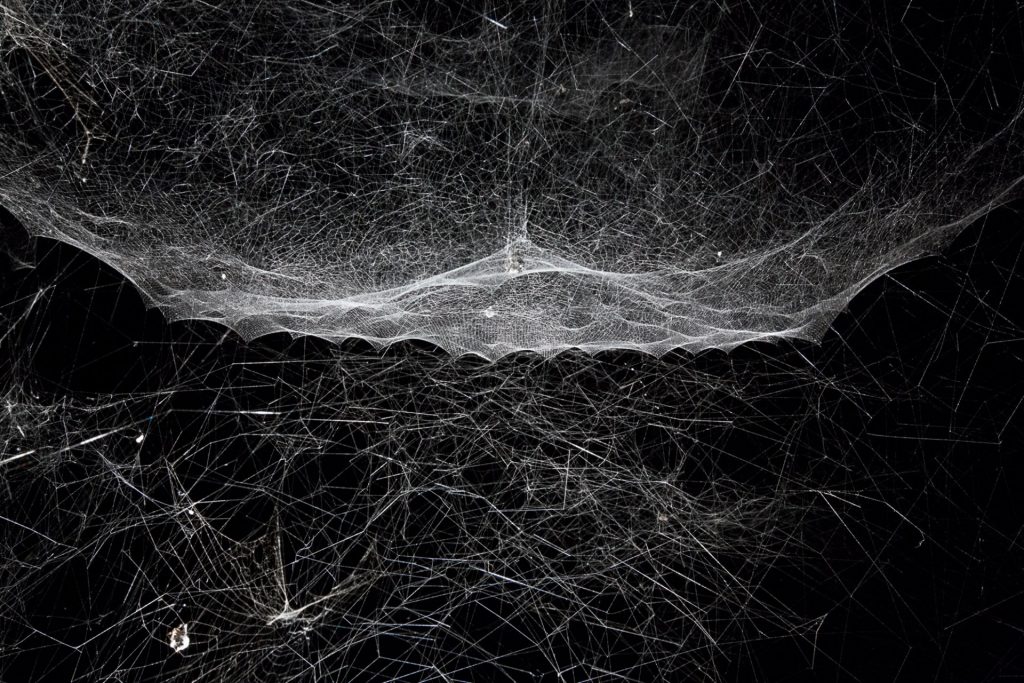

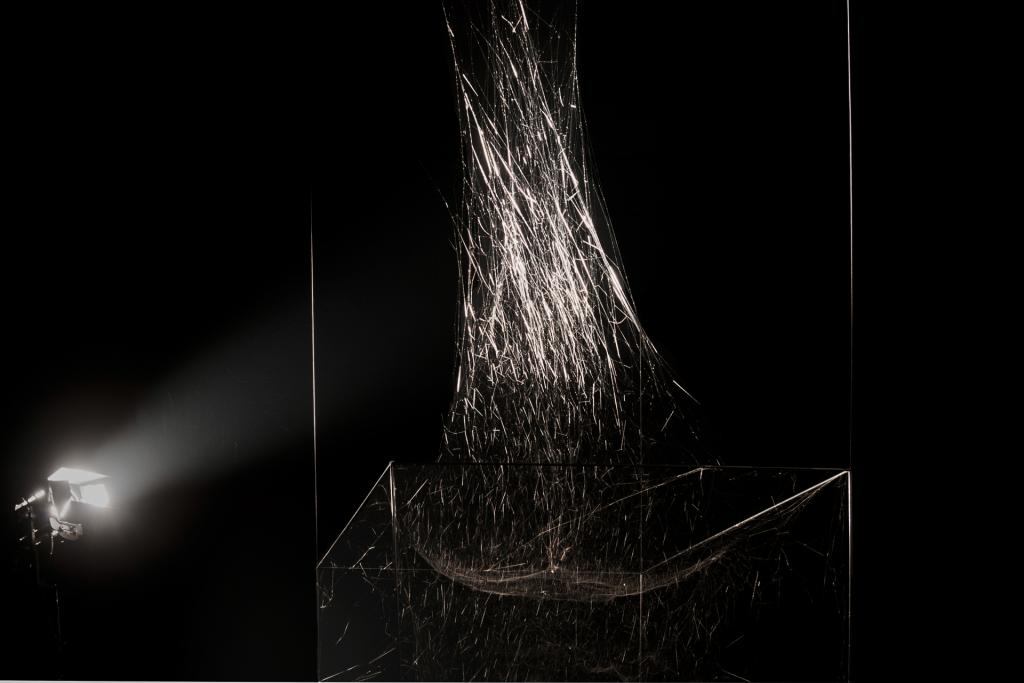

Additional works included How to Entangle the Universe in a Spider/Web?, which features the innovative, internationally recognized laser-supported tomographic technique developed by Tomás Saraceno with researchers at the Technische Universität Darmstadt. This allows for the 3D scanning, digitizing and reconstructing of spider/webs that resemble computer simulations of the cosmic web. With this technique—and the insights into invertebrate architectures that it allows—the 3D scan has inspired numerous applications from different fields of thought, including biomateriomics, group animal behaviour, cosmology and network theory. The full digital archive is accessible at arachnophilia.net. Elsewhere, Living at the Bottom of the Ocean of Air documented an Argyroneta aquatica spider as it breathes underwater, while the hybrid spider/webs that make up Webs of At-tent(s)ion revealed how different sensory worlds collide to create speculative architectures, encouraging the imagination of interspecies relations, communication and cooperation. Lastly, Untitled, Plinth to the unknown from I to III and the Invertebrate Rights series opened up new perspectives on our shared environment.

To join the song of air, we must attune more deeply to the interspecies language that surrounds us.

Learning with Nature

Interview of Tomás Saraceno by curator of Songs for the Air, Martin Faass

Martin Faass: Among the works which you will be showing in Darmstadt, there are three-dimensional sculptures, interwoven by unrelated spider species. How do you choose the spiders that create your art and where do you get them from?

Tomás Saraceno: Actually, the spider/webs choose me! There are myriad spider/webs already cohabiting with us: inside our homes, my studio in Berlin, across Europe, on almost every part of this shared planet. They’re also here in your museum, outside of these artworks! It’s just these other spider/webs did not arrive by invitation. With this exhibition, we hope that people begin to notice their spider/web neighbours differently; to move past personal or cultural arachnophobia. We want to acknowledge that living spider/webs face extinction—themselves becoming curious museological relics—if we do not recognize the violence of historical and ongoing extractive gestures, and shift our thinking about the ‘natural’ world.

Nature does not belong to us; we belong to nature. We have so many geopolitical projections borne from human exceptionalism, and yet spiders have existed for around 380 million years, while Homo sapiens only appeared 200-300 thousand years ago. Still we think we can “invite” spiders in. We have to see spider/webs not as pests, but as our predecessors and active co-creators of our lifeworlds. Some biologists say that any species needs at least 2 million years to truly understand how to live in a place. If we follow this logic, (some) humans have a long way to go.

MF: So you consider spiders as partners in your artwork?

TS: It is still very much their art; we produce it together.

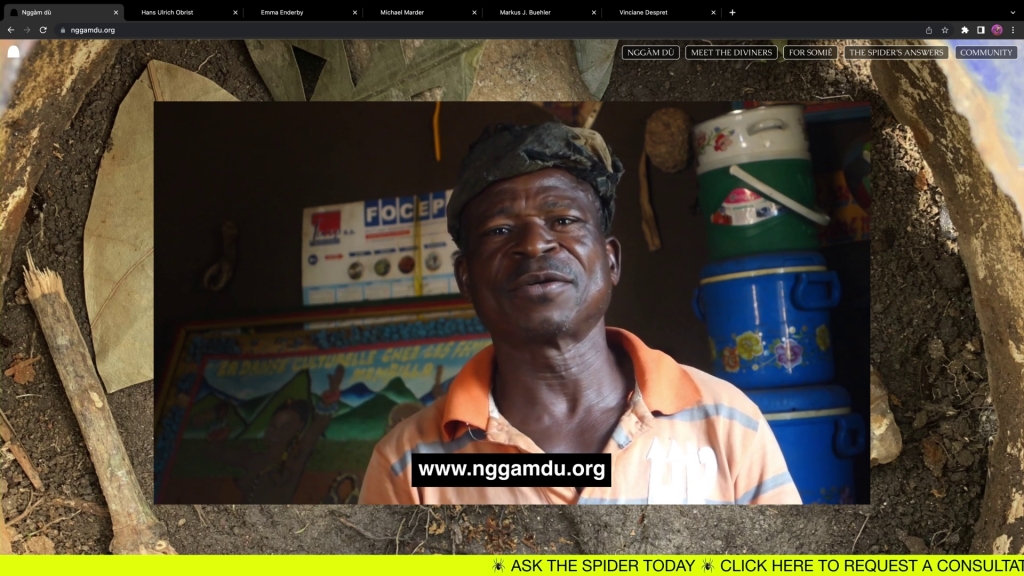

You can see this also in the app and project Arachnomancy, inspired by cultural traditions of spider divination, which invites users to have their future read by the spider/web oracles they encounter in their everyday, attuning to them in the process, and thus beginning to recognize shared responsibilities of care.

MF: How would you define the role that nature plays in your artwork?

TS: I don’t think of nature as a separate entity that can be integrated in my work. Humans have set themselves apart from nature, classifying it as an entity that is exterior to us. As a species we are fascinated with understanding others , but not necessarily their and our “Umwelten” or associated worlds, as Jakob von Uexküll put forth almost a century ago. This is why historically we have felt free to remove animals from their context and put them on display, like taking the spider from the web. As a species among many, spiders need and are deeply entangled with their environment(s), just as we need and are entangled with ours. To understand why we are facing mass extinction, ecosystems have to be thought of as complex webs of interaction and implication. A logic of human exceptionalism—or a separation of nature and culture—therefore misses the point.

MF: You want to establish a new connection between nature and history?

TS: History has always been natural! It’s a modern invention to separate “human” realms—art, culture, the social—from nature. This has been an important discussion in anthropology in the past twenty years, and more recently in the visual arts. Many interrogate the separation between nature and culture as a constructed and historical, rather than a real, innate distinction.

The idea that we can effectively separate the two in reality and not only in concept is pure hubris. Think of the “spotless” white cube museum or gallery—in actuality there are myriad particles, creatures, spiders, dust all present. And we clean constantly to try to get rid of them, yet they return. What if we just recognized these other voices? The artwork Songs for the Air sonifies the particles and dust through a technology we developed. Maybe the dust that gathers on top of vitrines and the spider/webs that adorn their shelves could tell us another history, if we found ways to attune you their forms of communicating.

Bruno Latour says that “we have never been modern,” that all these modern categories fail when applied to our experience. Museums are part of this project of separation but in fact they have never been modern either. We urgently need to let go of the ideas museums reiterate based on the supposedly “modern” divide between natural and cultural history, which, as Phillipe Descola writes, is a Western idea. You see how insidious it is when looking at what art gets put in art museums versus “natural history” museums—Western creations in the former and Indigenous, African, Asian, in the latter. We need to unpack where these divisions come from and why, to decolonise our thinking and understand better the complex web of relations we are part of.

MF: Darmstadt, specifically the Technical University, was in a way very important to develop some of this technology you mention, wasn’t it?

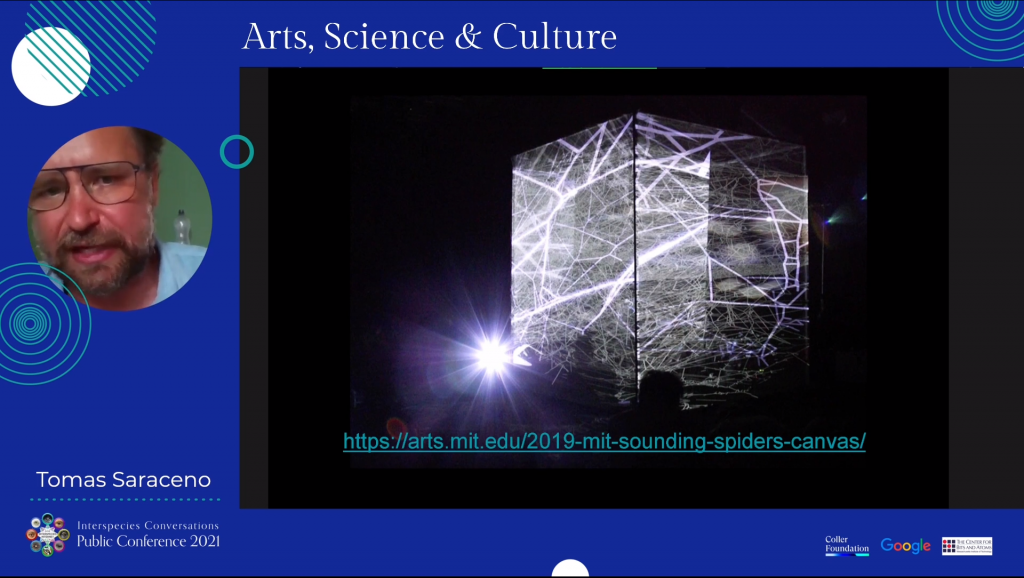

TS: Yes, over ten years ago I worked with the TU’s Photogrammetric Institute to create an original laser-supported tomographic method for achieving the first ever 3D spider/web digital scan.This technique has sparked many amazing knowledge paths, and we continue to expand its possible applications—most recently through an ongoing collaboration with Professor Markus Buehler at MIT. The aim is to make a 3D spider/web archive available to collaborators, to share knowledge and learn more about entangled spider+web ecologies. Also, in 2016 in the context of 48th International New Music Festival, Darmstadt, I am so proud to say that in the place where John Cage and Stockhausen gave their seminal lectures, we gave voice with a nonhuman concert with spider/webs. I’m especially happy to come back with a new ensemble, sonifying the air!

MF: So it’s great that the project we are working on has so strong a link to Darmstadt after all these years.

TS: Yes, so beautiful. I am happy to be back. I was also able to meet Peter Jäger, Head of Arachnology at Frankfurt’s Senckenberg Natural History Museum; a great friend of mine that I have been collaborating with for more than 15 years.

MF: Finally, what do you want everyone to take away from this exhibition?

TS: I think firstly to recognise the term spider/web—which respects the interconnectedness of a body and its world—and to work together to sense new threads of connectivity, moving from arachnophobia to arachnophilia! It would be great if we could all consider also the role of the museum and listen to voices that ask for repatriation of museum objects. This is an important contemporary conversation. We may think about it in relation to cultural heritage, but I also want to think about reparation in the context of our “Umwelten”. What needs to be given back to nonhumans? And how, by sonifying particles in the air, the audience begins to think about their own Umwelt, which includes pollution. What if we could repair carbon emissions and redistribute wealth gained by more affluent countries who for too long have offloaded toxic consequences onto the Global South? Is this kind of reverse migration a form of decolonisation as well? Decolonize the air from phobias to philias, and allow the atmosphere to enter a new era of solidarity.

...