...

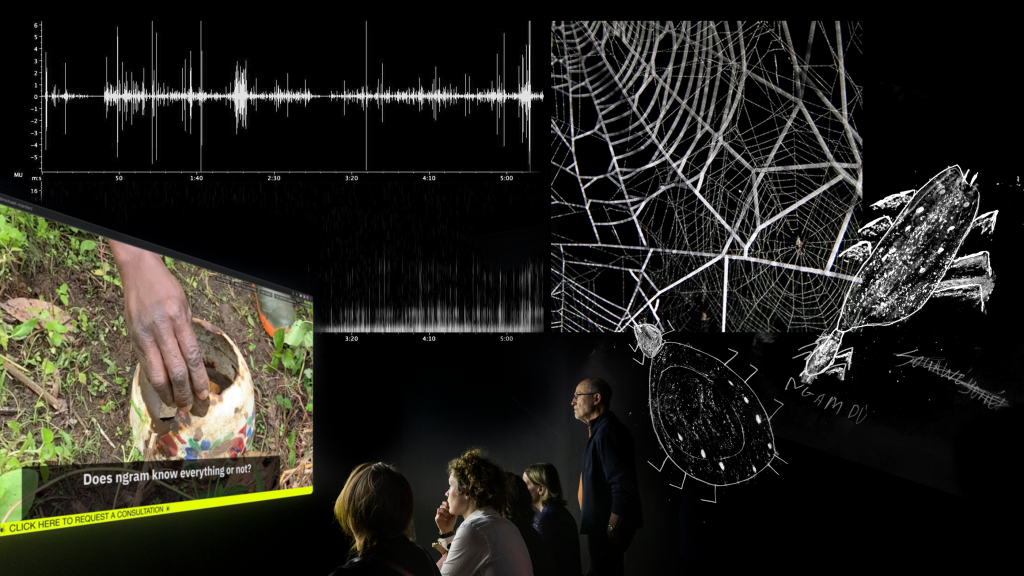

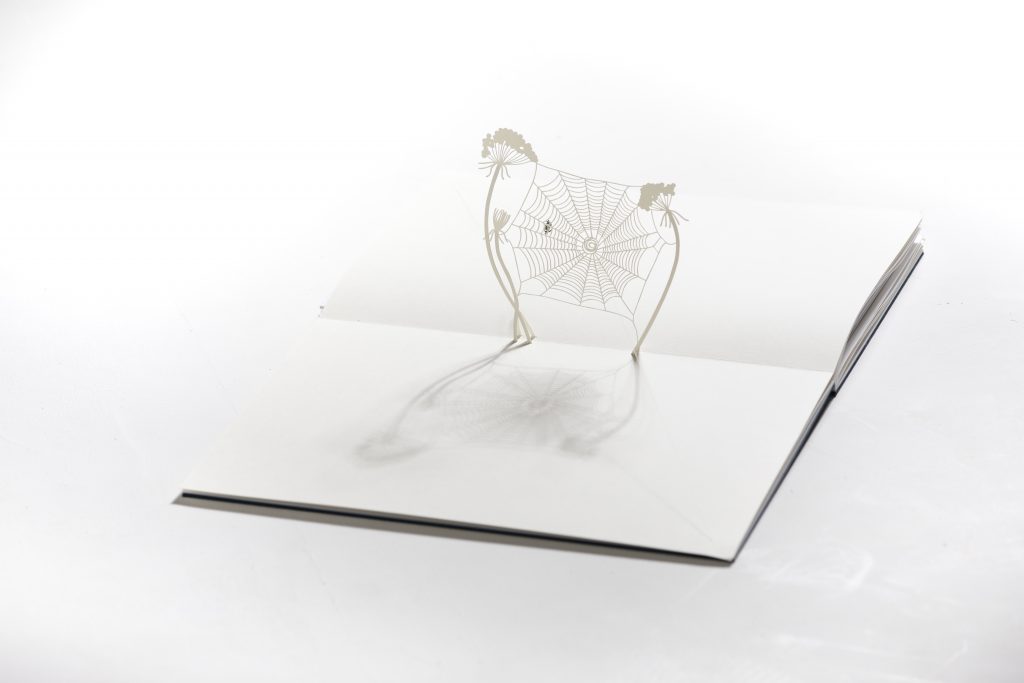

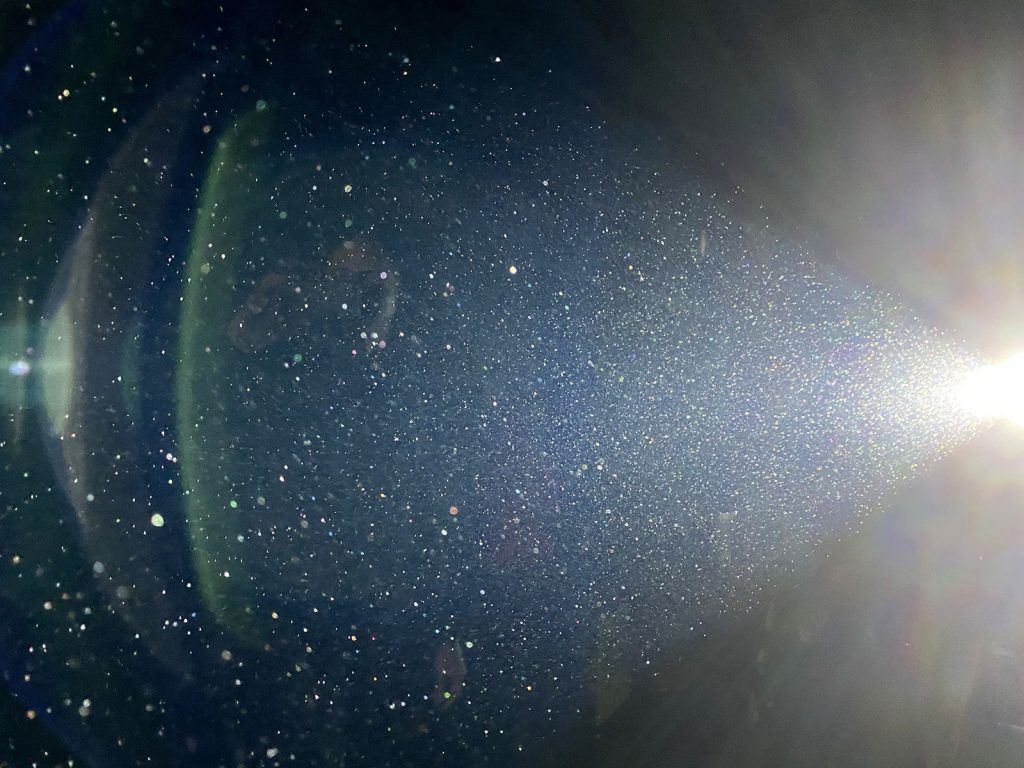

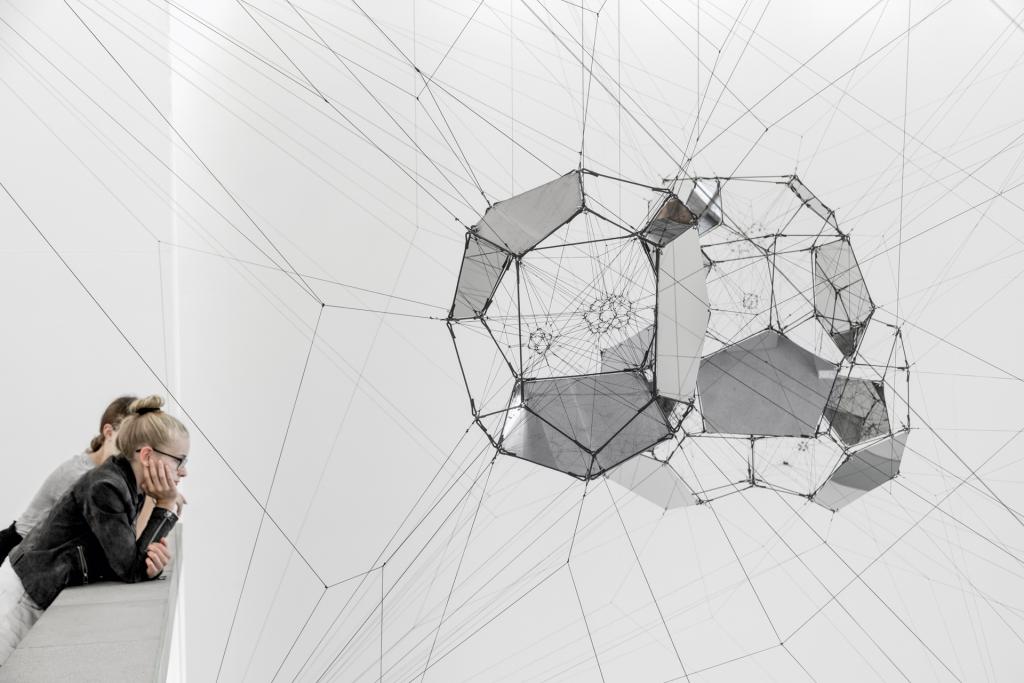

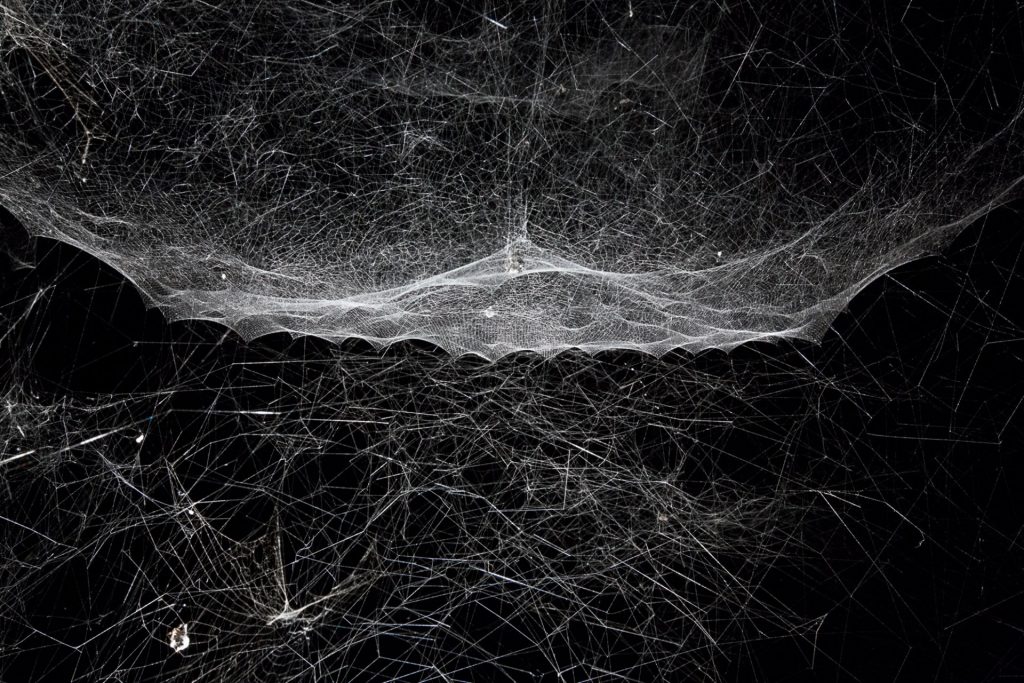

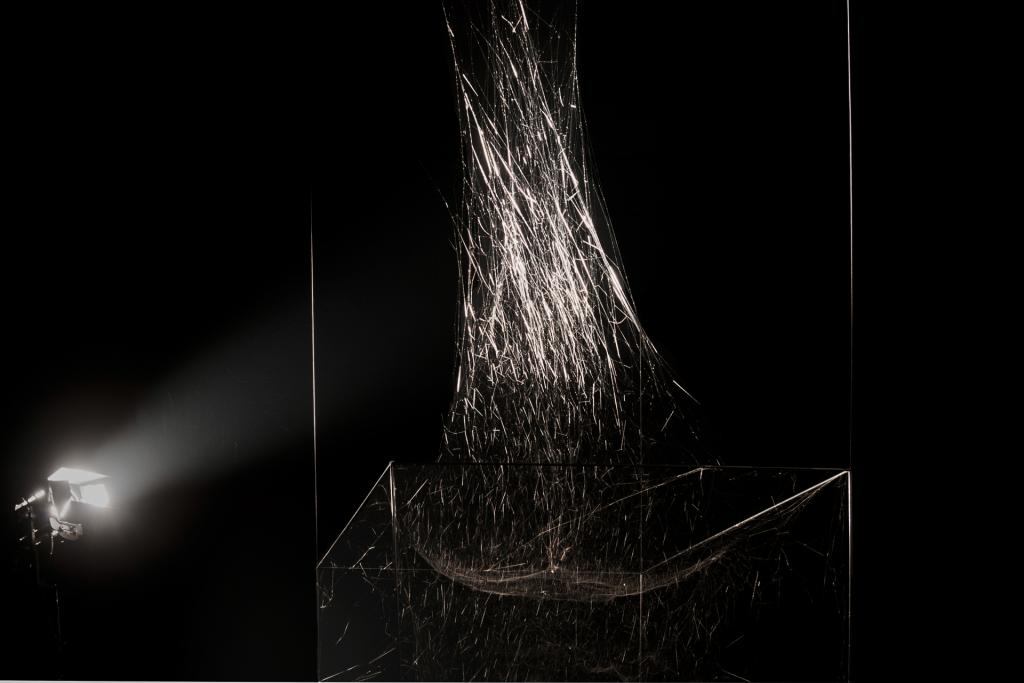

Meeting Atrax robustus and cave spiders/webs, in Australia’s Blue Mountains with Dr. Helen Smith, Dr. Jonas Wollf and Tomás Saraceno in 2018, friends of Arachnophilia.

Photography by Studio Tomás Saraceno.

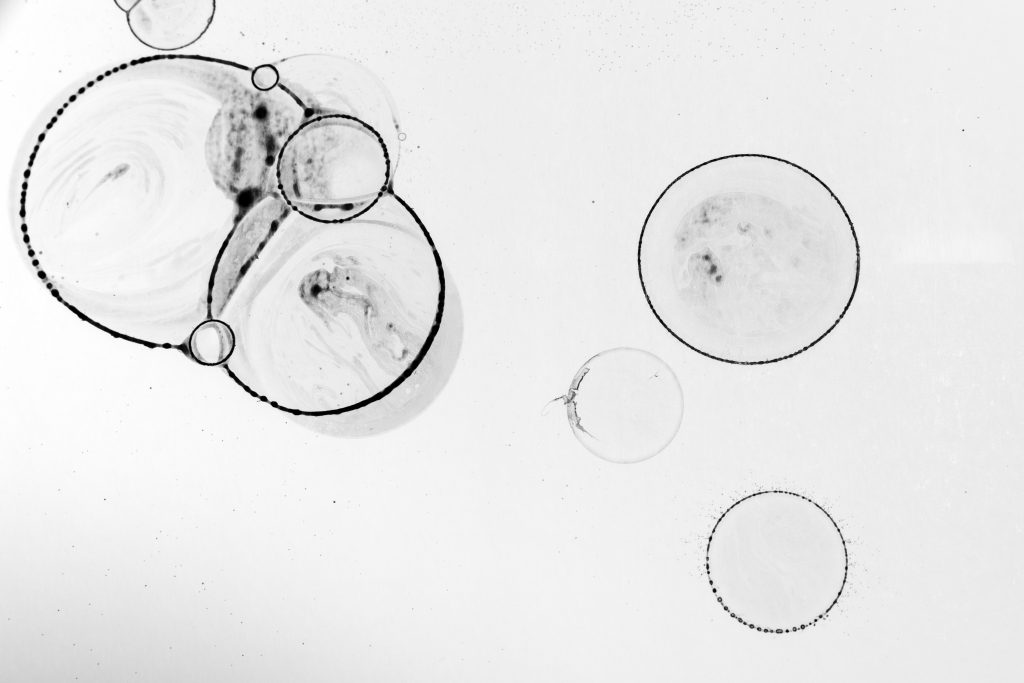

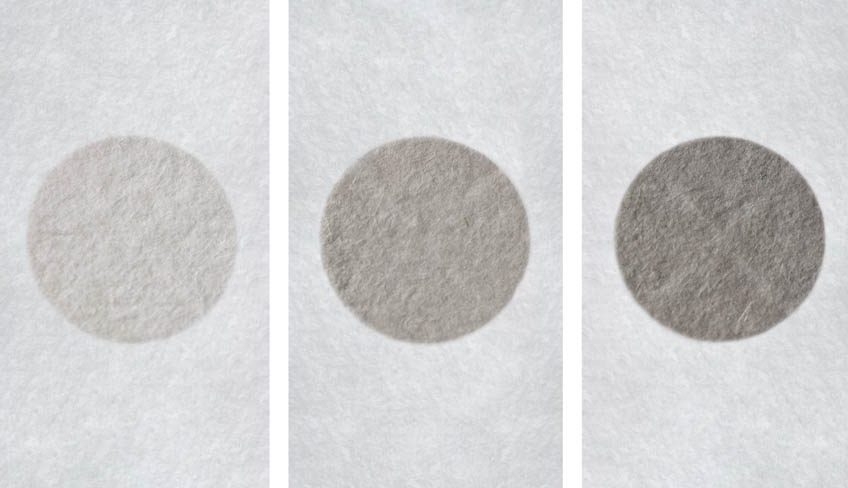

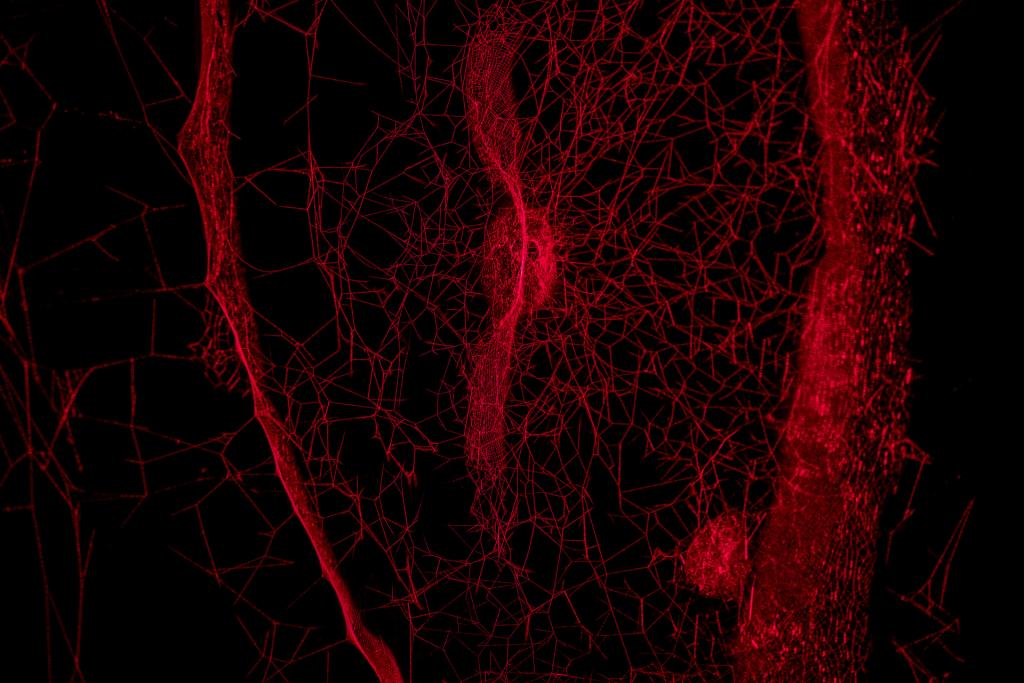

BAM pollution monitoring tape from Australia for We do not all breathe the same air, 2018 – ongoing

Photography by Studio Tomás Saraceno.

“First and foremost, Tomás is a collector of perspectives, looking at the world through many eyes. He is as invested in the conversations which form the foundation of his works as he is in their astonishing outcomes. As a recovering arachnophobe, I have Tomás’s gentle and beautiful interspecies collaborations to thank for reminding me of my own connectedness, from pollution particles to sound waves to the cosmos..”

– Emma Pike, Mona Senior Curator

When Tomás Saraceno first came to lutruwita/Tasmania, he was struck by how clearly its plant life reflects the intersecting of colonial with Aboriginal histories. Native and introduced plants are now entangled with one another, he says, their relationship reflecting an almost 250-year-old story of conquest, displacement and disruption. Aboriginal people had lived for some 40,000 years in lutruwita before Europeans settled, built and farmed on their land.

In Tasmania, there is only one native deciduous tree or shrub, Nothofagus gunnii, also known as the tanglefoot beech or ‘The Fagus’, and it’s restricted to mountainous wilderness. As botanist Greg Jordan explains, extinct relatives of this Fagus once grew across the supercontinent Gondwana and it has survived to evolve in the ancient, wet, open, fire-free mountains of western Tasmania through tens of millions of years, while the areas around have become drier and more fire-prone. In preparing this new work, as he learned more about the Australian environment, Saraceno moved from his previous European focus on seasonal cycles to an interest in the effects on different vegetations of sunlight and heat and of fire or its absence. How do shapes and textures change, as well as colouring? How, he asks, might we perceive the chemical threads that silently bind the web of life? He is especially interested in the different effects between out-of-control bushfires, intensified by drought, and carefully orchestrated cultural burning by Pakana custodians of Country.

Unfolding across six panels of foliage, you can see delicate crinkle-cut leaves from Nothofagus gunnii, alongside those of both native and introduced plants collected in the grounds of Mona and further afield in lutruwita. There are leaves burned by intense fires and by slow fires. Leaves pressed like botanists’ specimens, others picked and dried, still others fallen naturally from the plant.

How do natural vegetal pigments behave under varying conditions—sometimes catastrophic—and now inside a museum? How will the leaves you see here alter over time? What do living organisms tell us when we pay them close attention? Emma Pike, curator of Saraceno’s exhibition at Mona, believes that being here in Tasmania took his ongoing projects with leaves and flowers down unexpected pathways and may be just the start of a new body of work.

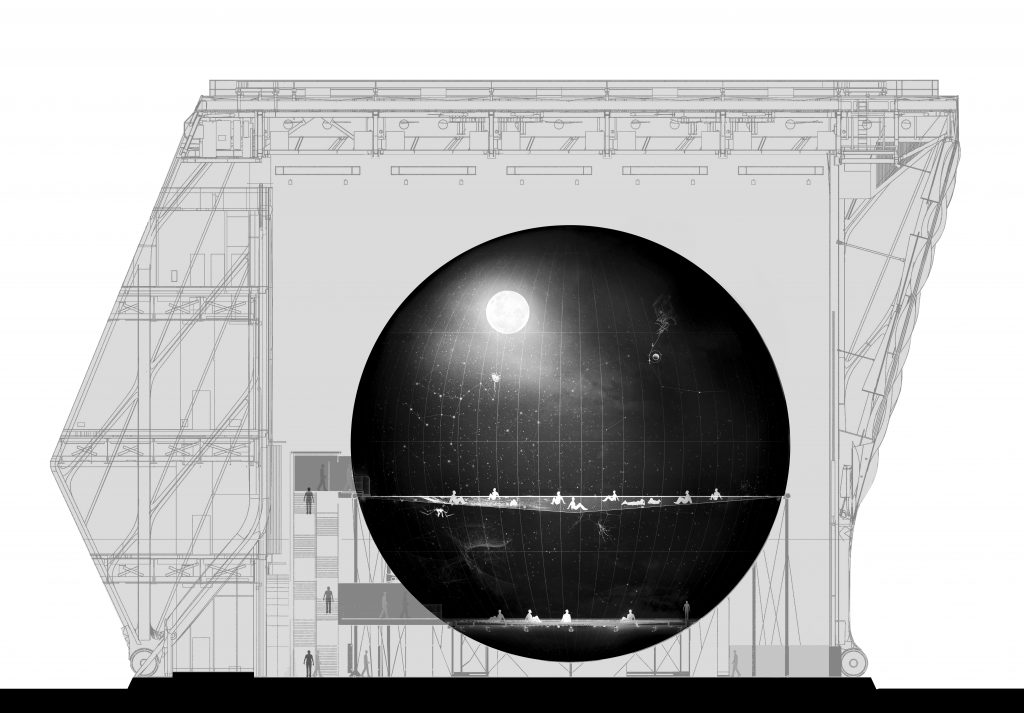

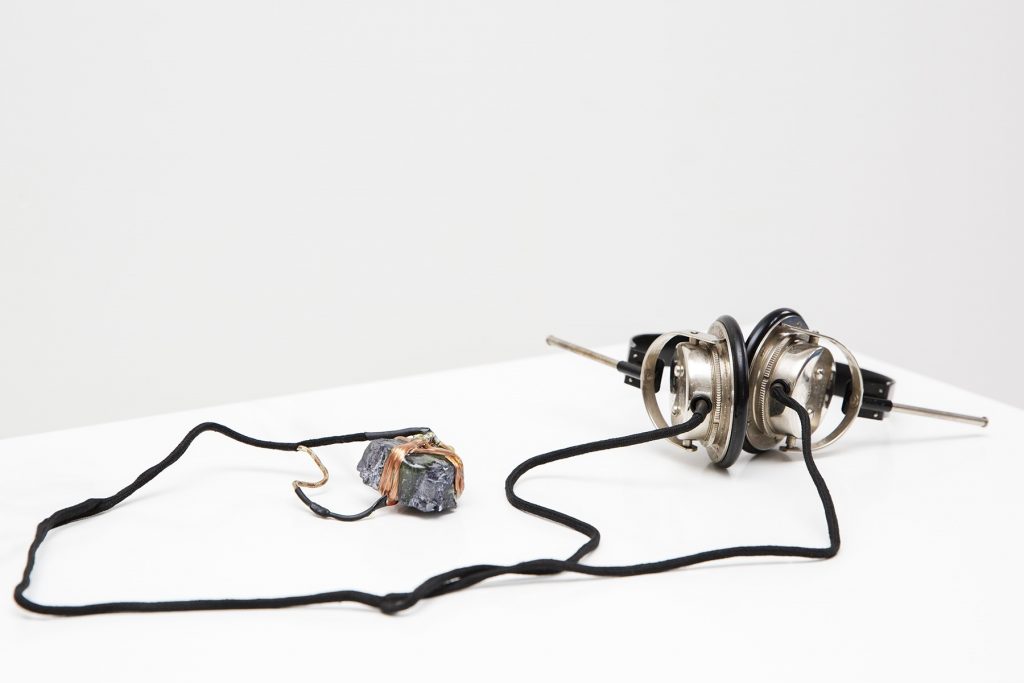

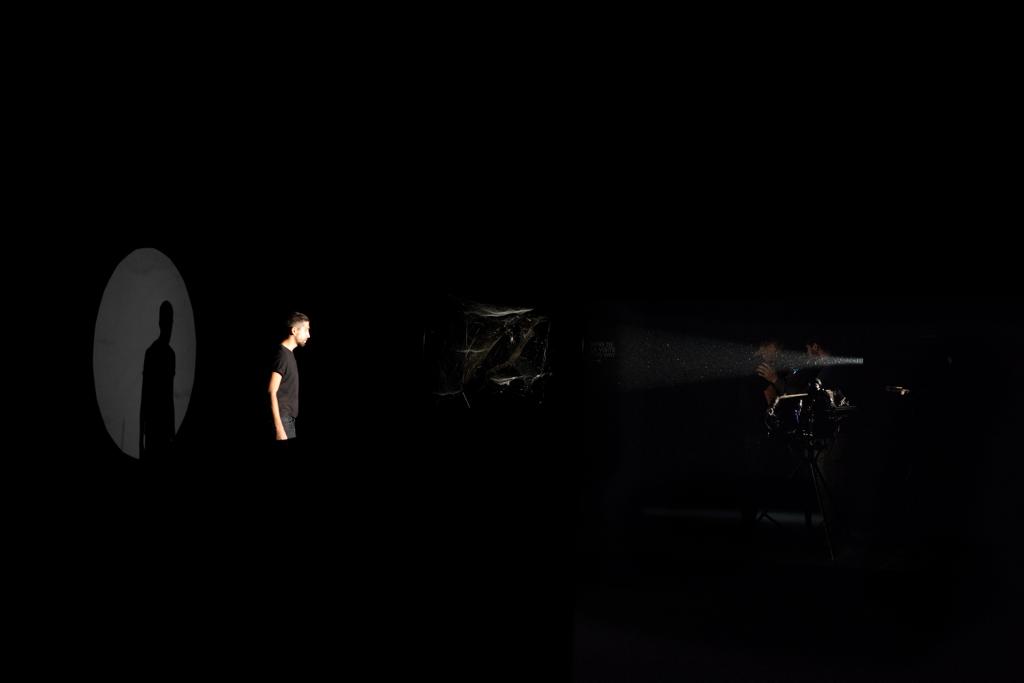

Works exhibited as part of Oceans of Air are made from

an array of materials including lighter-than-air Aerocene sculptures, fine particle pollution from the skies of Mumbai, air quality samples from across Australia, dust from the museum, radio waves streamed from First Nations Argentina, radio frequencies generated by meteoroids penetrating the earth’s outer atmosphere and recorded from the roof of Saraceno’s Berlin studio, and the leaves of Tasmania’s only deciduous native tree.

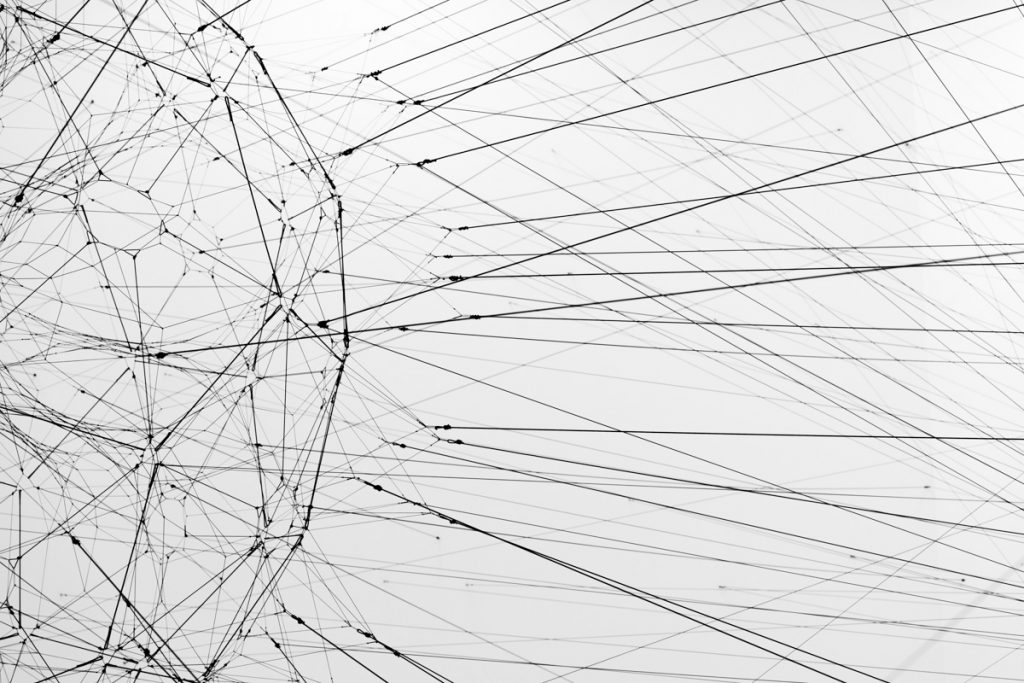

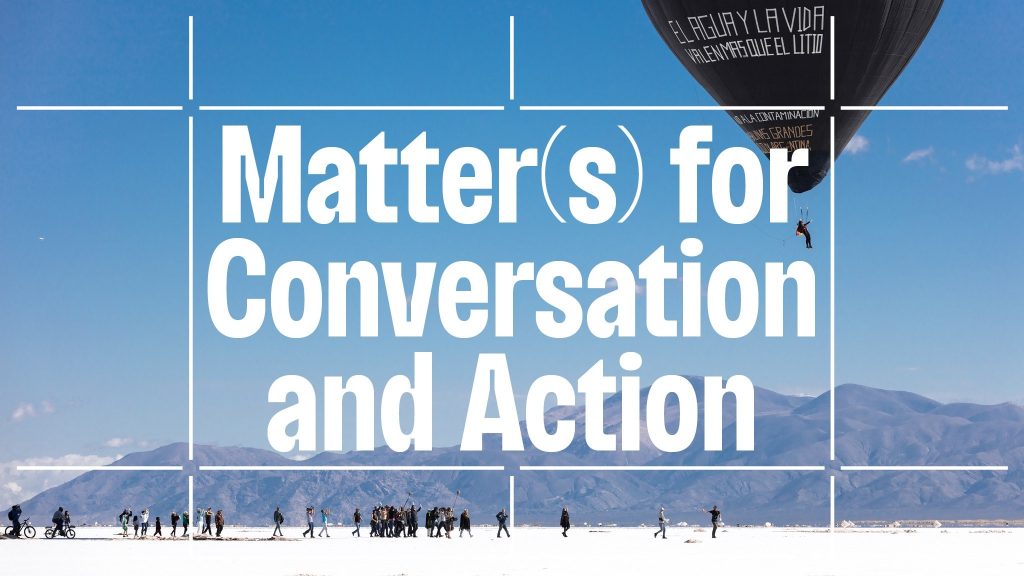

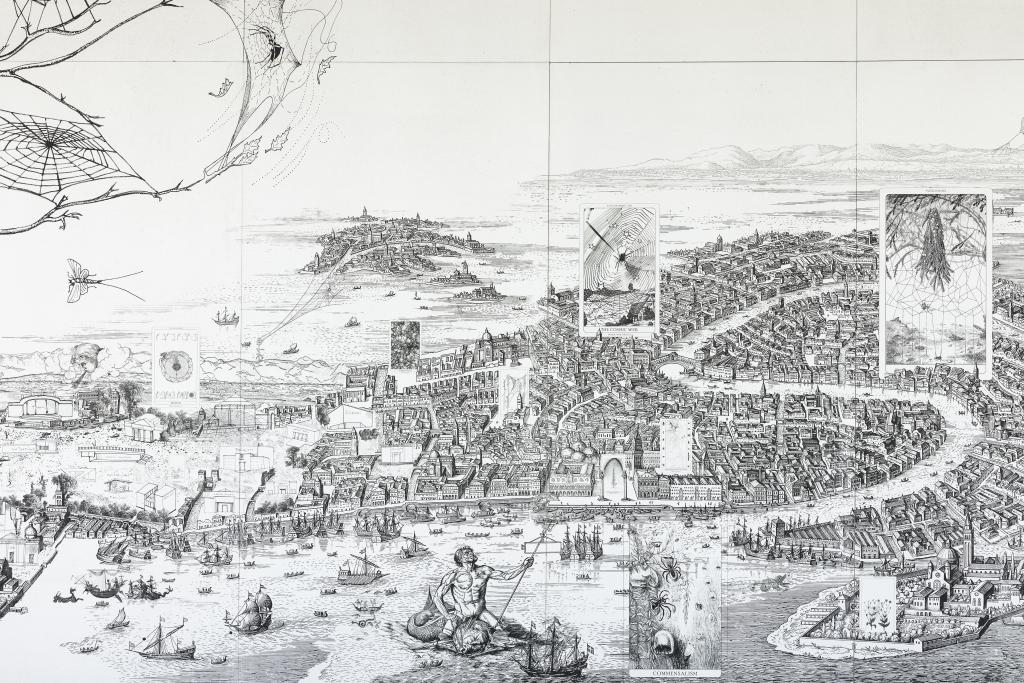

In a call for environmental justice, Saraceno collaborates with and contributes to communities and species that have been impacted by the Capitalocene in solidarity with Earth, the air, and the cosmos, particularly as part of the open-source community projects Aerocene and Arachnophilia.

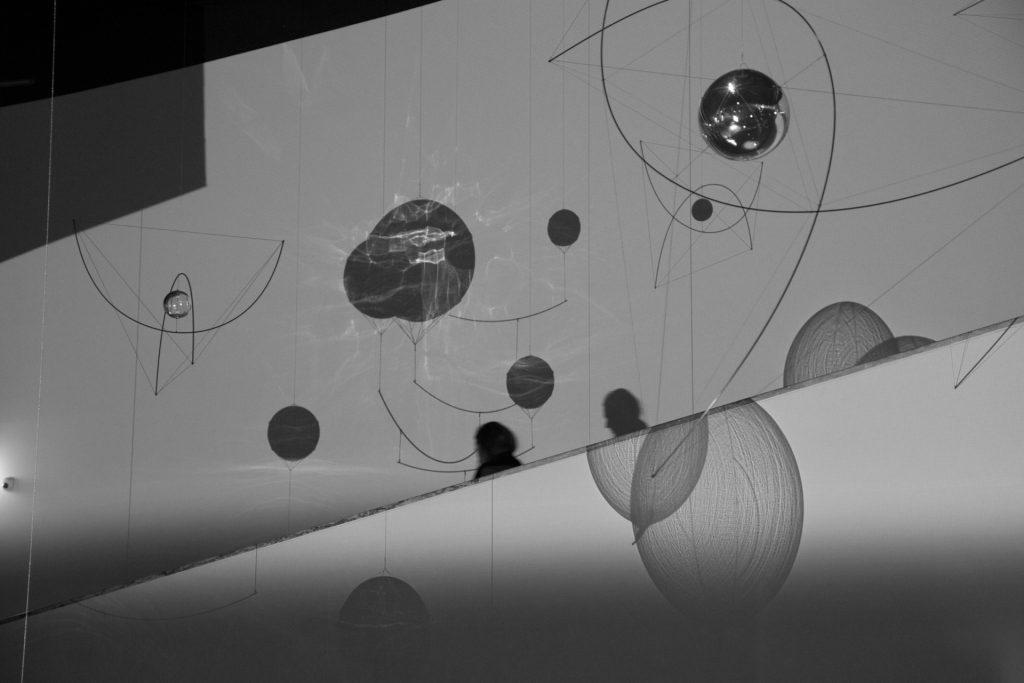

Tomás Saraceno, Silent Spring 18052021, 2021. Photography by Studio Tomás Saraceno. Courtesy the artist.

Encountering Tasmanian flora towards LEAF, LEAVES, LIFE, LIVES, 2022.

“We live entangled lives, and as Torricelli, a student of Galileo once said, we are all always ‘living submerged at the bottom of an ocean of air’. The air itself is restless, constantly in motion. The humans of the Capitalocene, caught in the undertow of extractivist ethics and the rhythms of capitalism, have toxified the air, rendering it unbreathable for many and forcing new regimes of inequality upon us all. Oceans of Air flows towards shared responsibilities with the worlds we inhabit, knowing that not all have the right to breathe, and that not all breathe the same air.”

-Tomás Saraceno

...