...

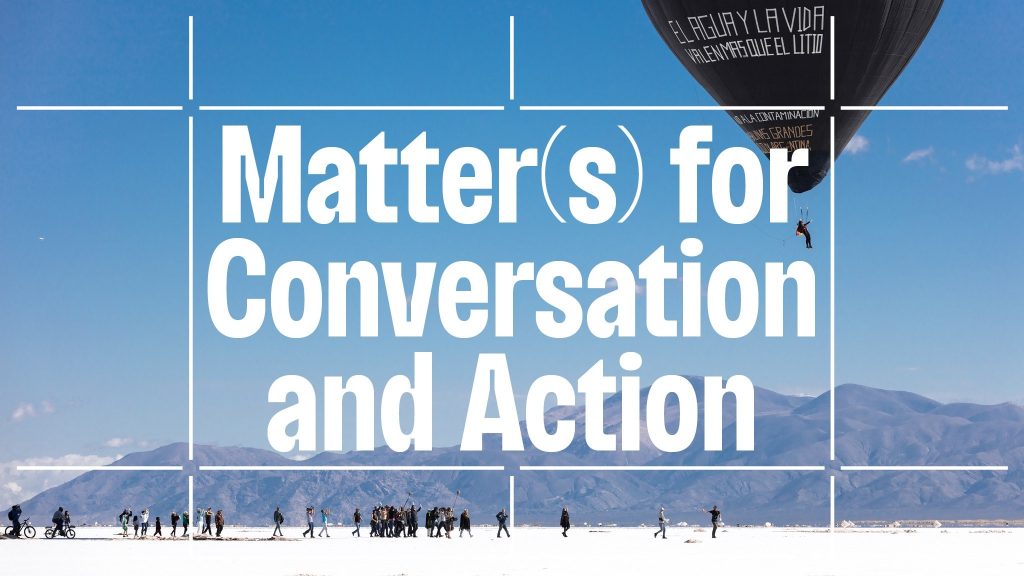

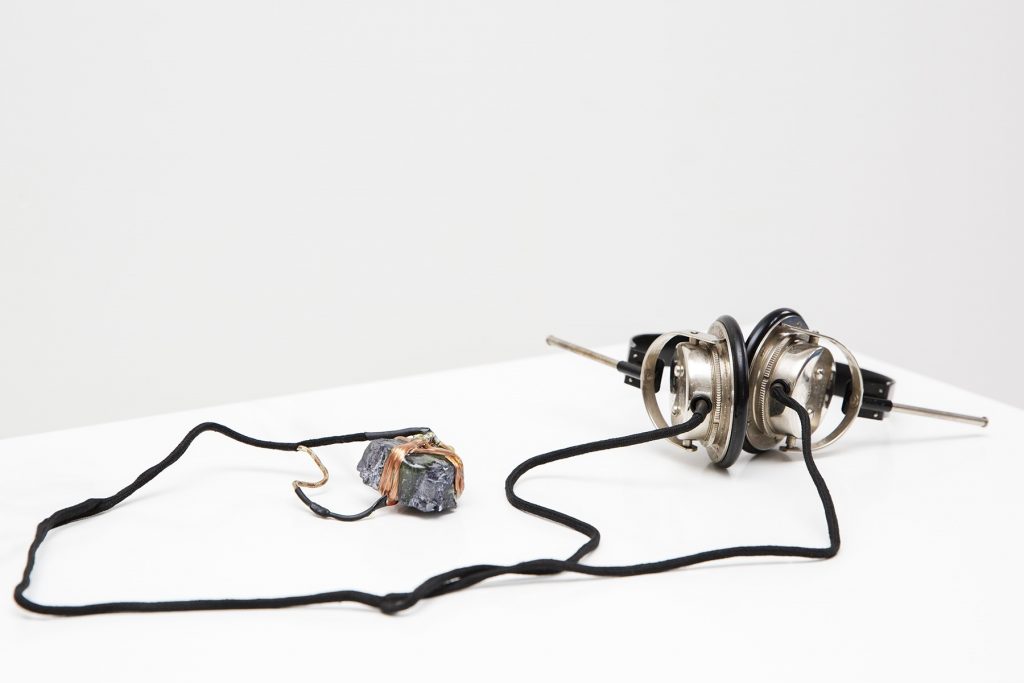

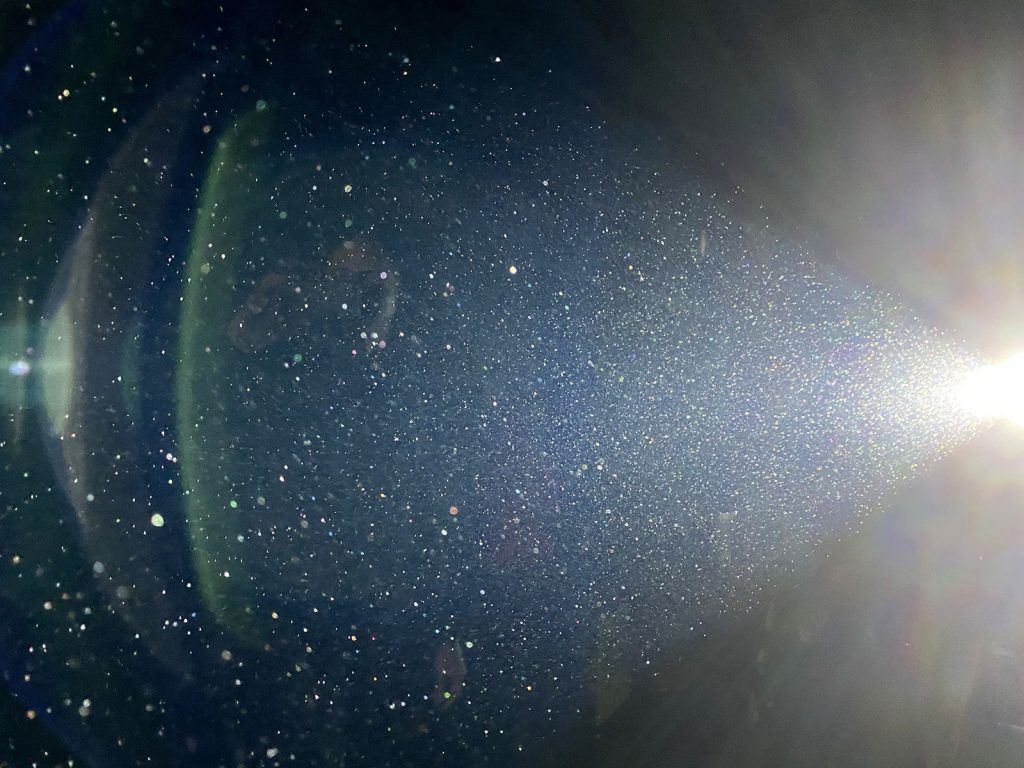

What you see, as in the sky, is always the past… It is, actually, the light that was emitted from the Large Magellanic Cloud 163,000 years ago… We, earthlings, are always convicted to watch the past… 163,000 Light Years is a project developed during a field trip to the Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia in 2016, a place where when a thin layer of water covers the salt flat, the horizon is erased and the surface becomes a mirror for universes.

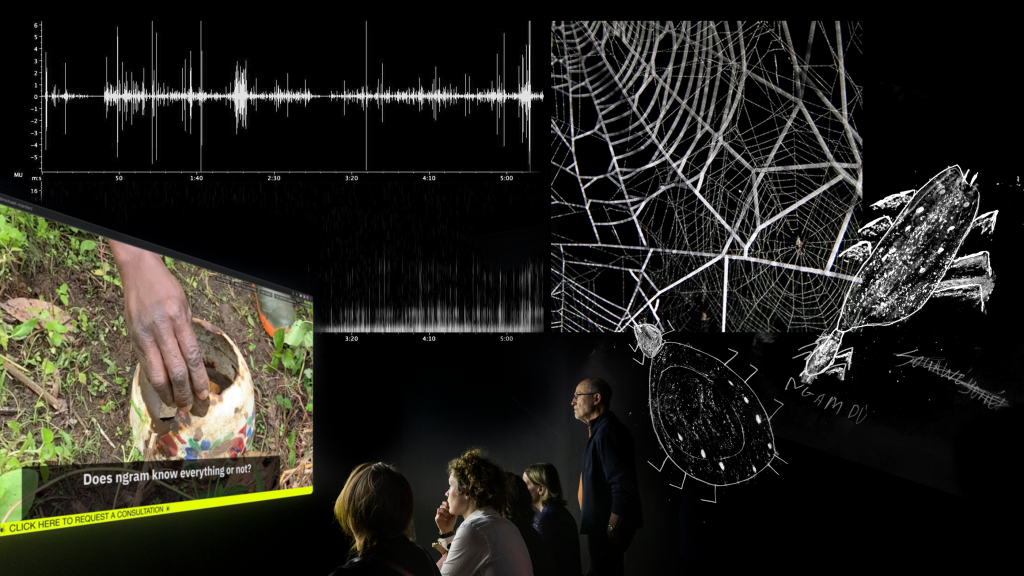

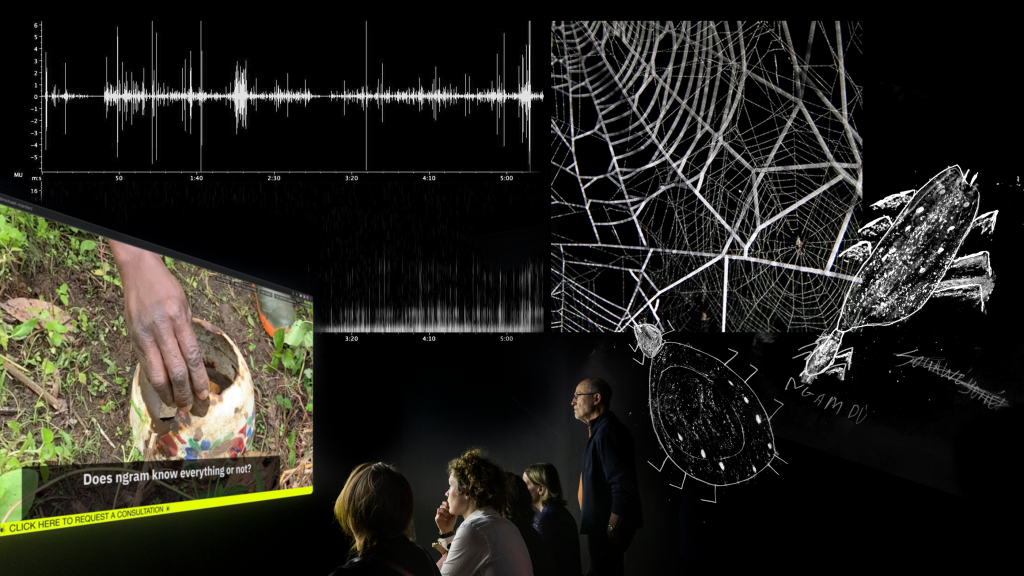

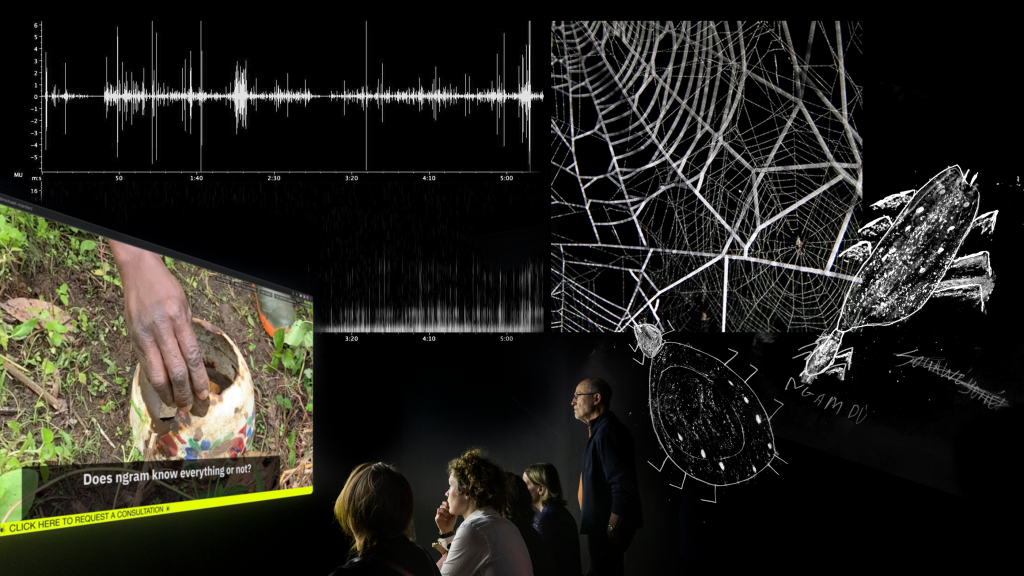

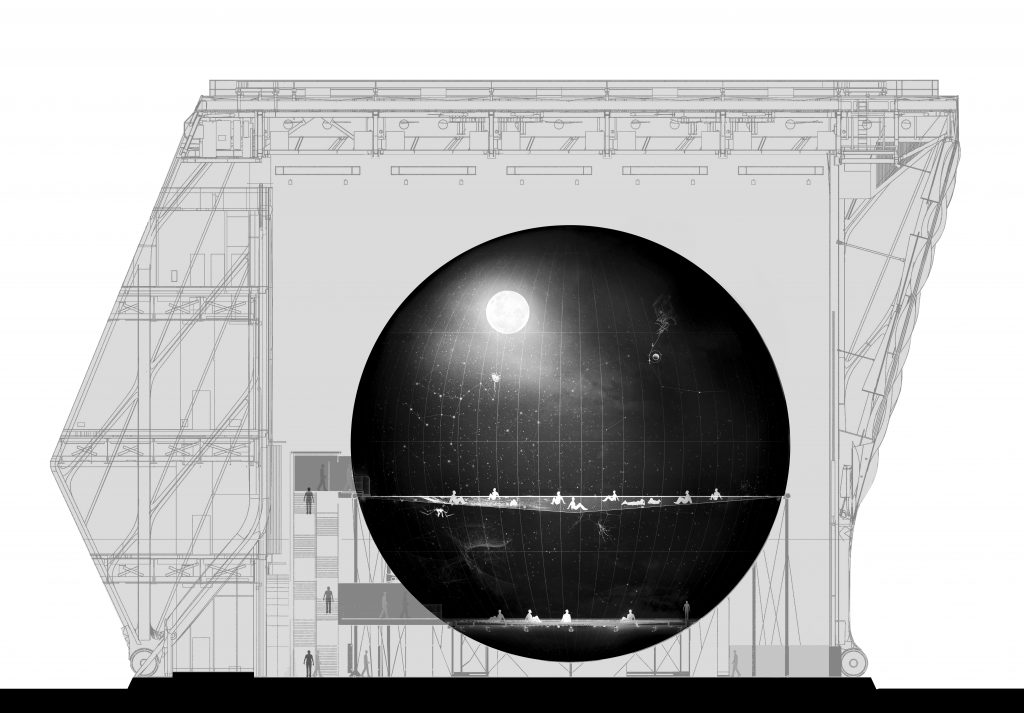

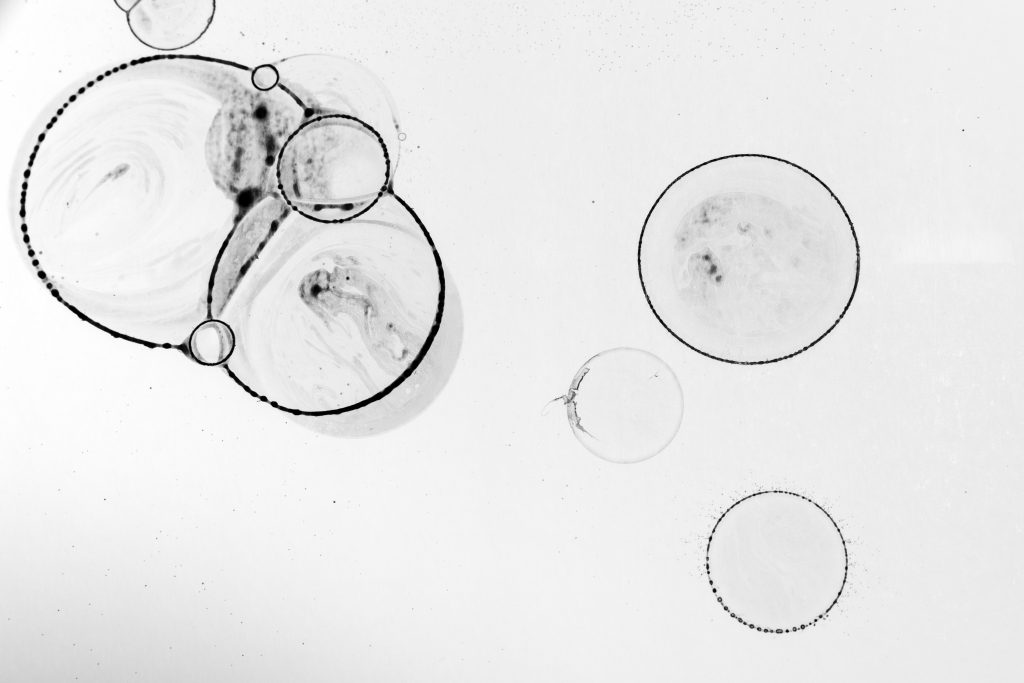

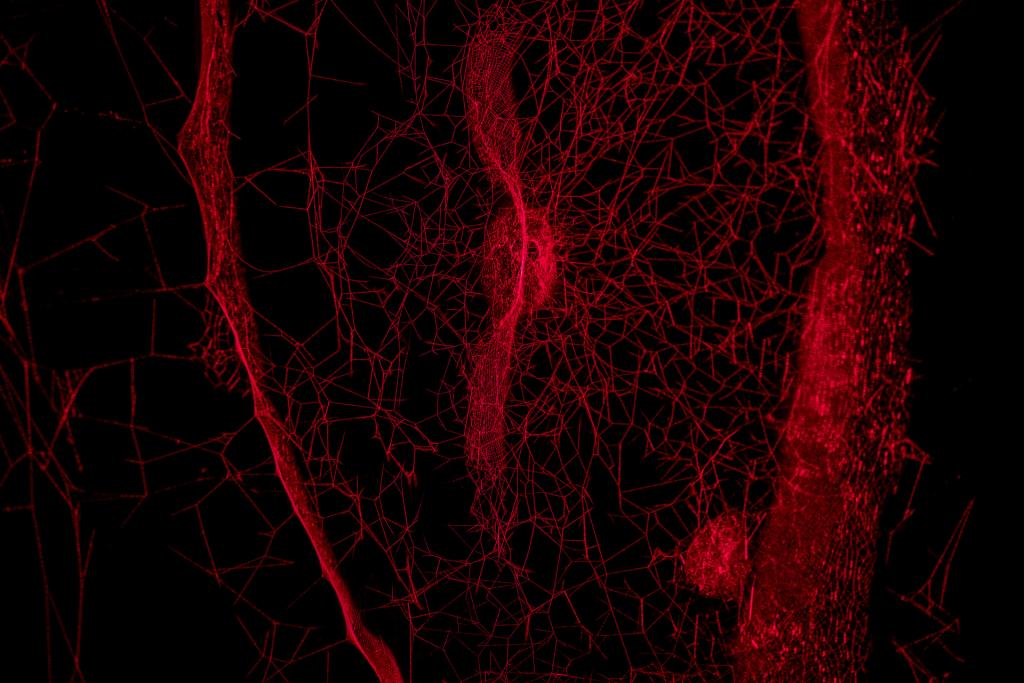

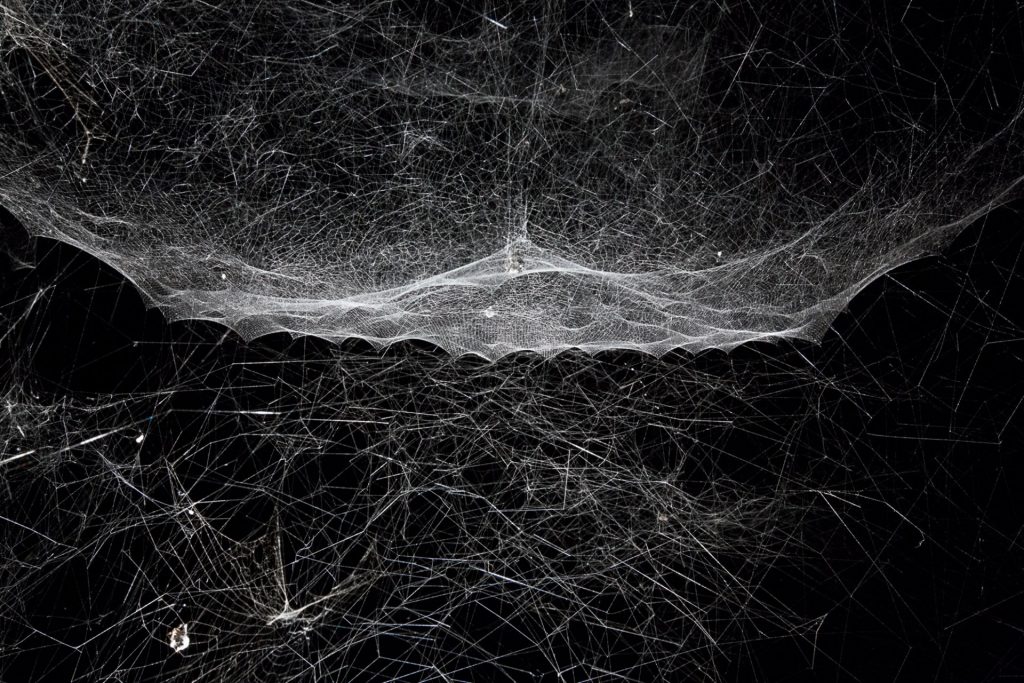

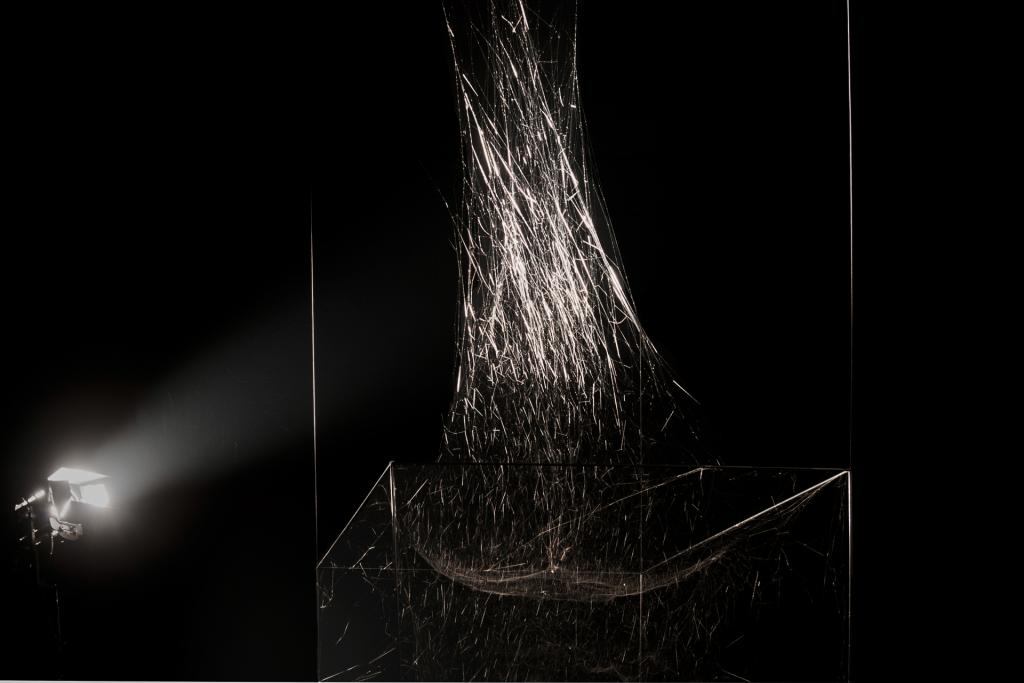

Similarly to the waves that animate the surface of the salt flats in Uyuni, Bolivia, where the film 163,000 Light Years was shot, gravitational waves ripple spacetime in waxing and waning movements warping a linear conception of duration. Recordings of Magellanic Clouds, two galaxies which are 163.000 light years away from us, intersect with the rippling sound two black holes colliding. Different temporalities appear, dimensions are projected, and epochs redefined. This is the light seen by the prehistoric spiders… We are entering a new dimension, a new Era, from the Anthropocene to Aerocene… 163,000 years in action now…

163, 000 Light Years

Gonzalo Ortega. Uyuni presented you with the possibility of documenting the night sky by way of its reflection on the largest flat saline surface in the world, and this generated a series of specific pieces. What triggered your interest in working there?

Tomás Saraceno. I love how the cosmos reverberates in Uyuni, like the recent ripples of two black holes colliding a billion light years away, providing the soundtrack for the video piece 163,000 Light Years.

The duration of an average sidereal day is twenty-three hours and fifty-six minutes. But the duration of a solar day is twenty-four hours, since the Earth needs four minutes more to compensate for the rotation of the sun. The difference between these two units reveals discrepancies in our articulation of time, which throughout [the] history [of reason] has become linear and one-dimensional, losing its potential multiplicity. We have to be willing to return to the idea that different times could co-exist simultaneously—times that were already there when this whole “cosmic spectacle” started.

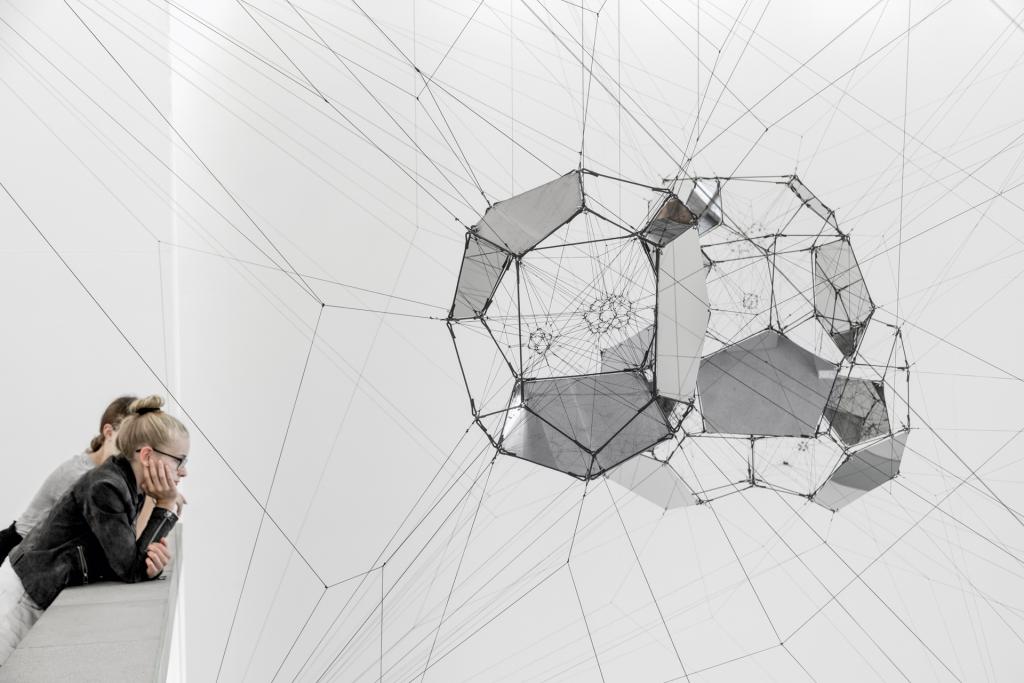

GO. In previous works you’ve made reference to Membrane Theory, according to which any modification to a surface provoked by agents—in this case human beings (i.e., visitors to the exhibition)—generates a deformation, a curvature, an alteration in space and time. In an amazingly precise way, this formal analogy in your pieces alludes to the notion of cause and effect, and how that which is generated by some has effects on others. However, at the Salar de Uyuni, the surface is inescapably flat. Is there some analogy with Membrane Theory here?

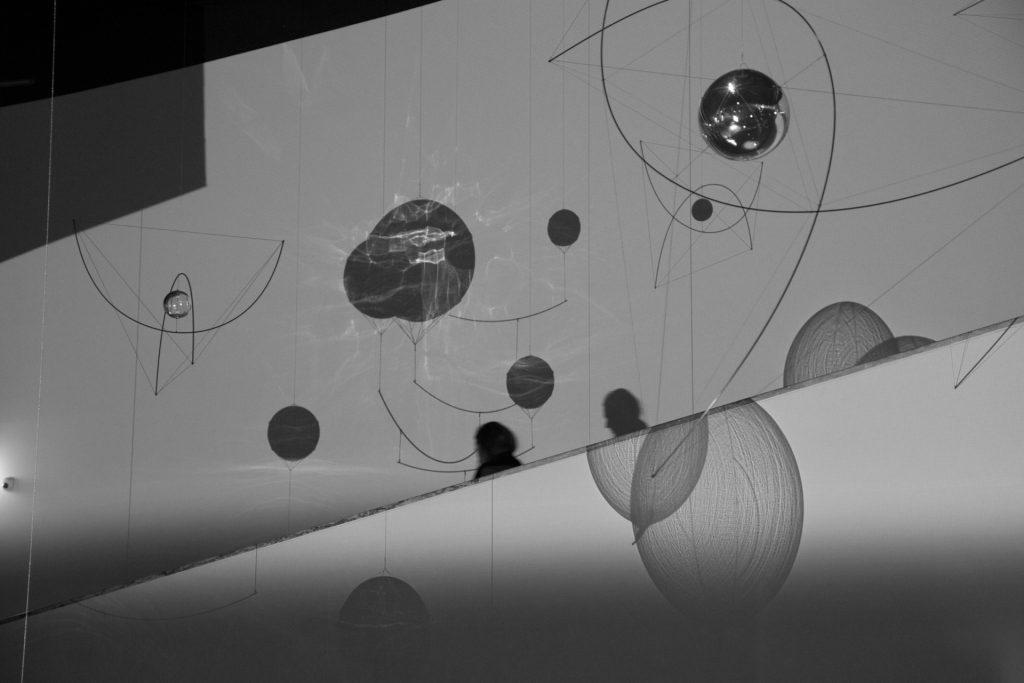

TS. I love it when horizons disappear. [In Uyuni] you don’t get a mirror image! The image isn’t reflected. You find yourself inside of it, but not in a symmetrically reflected image; you don’t cast a shadow; instead, you get the reverberation of a continuum. When the surface of the lake ripples, the reflected star-scape ripples too, making these gentle time-space wavelets, bringing two distant stars or cloud galaxies closer together and further apart. You’re treading upon the cosmos, upon the stars and galactic clouds, lithium deposits, more disorientation. North gets reset, and it’s no longer possible to orient yourself. After a month there, you can feel that you are a cosmic being.

GO. And there is no precise notion of the horizon. Taking a look at your pictures, there is no well-defined line, not only in terms of the actual Earth’s horizon, but also in terms of where you are standing in some of the pictures, for example, and also your reflection on the ground, on the water. That’s not to say that you’re exactly aligned with the horizon—it’s more as if the two have merged, a complex moment when two realities come into contact with each other.

TS. What I find fascinating is when it comes to the idea of a surface that has been used to calibrate telescopes from outer space: the analogy of humans trying to find life on another planet, and the analogy of telescopes; the fact that human optical devices to seek life forms in outer space have been tuned using this surface, under which a cyanobacteria, the ancestral producer of oxygen, lives.

GO. I’d like for you to explain how the two experiences in Uyuni ten years ago differed from this most recent one. What changed, in your creative processes and in how you understand this place?

TS. On the second journey I focused on making images and trying to record what happens during the night. That was what I was interested in: not only to record, to memorize, to be, during the day, but also during the night. It was a big change: I decided that the first experience was mostly about the day; the second experience, ten years later, was all about the night. We spend one third of our lives in another state of consciousness: our dreams. Maybe I needed to do something along those lines. There is perhaps another reality that we might touch upon, and I like to think that all artworks exist in a moment that has a different temporality, overall. We didn’t have direct access to the pieces’ end product, how they will be presented, exhibited, titled, nor to what we have recorded, either because we fell asleep or into another dimension, or because we didn’t have the time. On this second journey, I was trying to shift my perception, to focus on things I wasn’t closely observing on the first trip, but they were there: meaning that it [depends on your] focus, [on where you] focus your lens.

GO. I’d like to point out that the Uyuni salt flats are a good fit with your way of thinking about creative processes, because they involve certain elements that, as you say, alter one’s state of consciousness. They confront you with a reality unlike anything we can see anywhere else on Earth. In this way, you transport us to a territory of dreams; it’s something fantastic, almost oneiric. What did it mean to you to document this, and on this second trip, to develop a parallel production concept, bringing in a group of experts, moving in equipment, with forethought, a set idea? I’m guessing that it involved something like moving between two worlds, wouldn’t you say? I’m trying to reconcile the magical experience of being there with a production that was very precise in logistical and technical terms.

TS. The video piece 163,000 Light Years lasts for 163,000 years. In other words, very few people (or whatever there might be in the future) will be able to view this piece. It’s possible that human beings as we know them, Homo sapiens, will have vanished and form part of the past, or maybe not. But this is a piece—a video—that takes 163,000 years to unfold. I wonder about the extent to which the technique for recording a phenomenon with such a long duration also coincides with the duration of certain species on this planet.

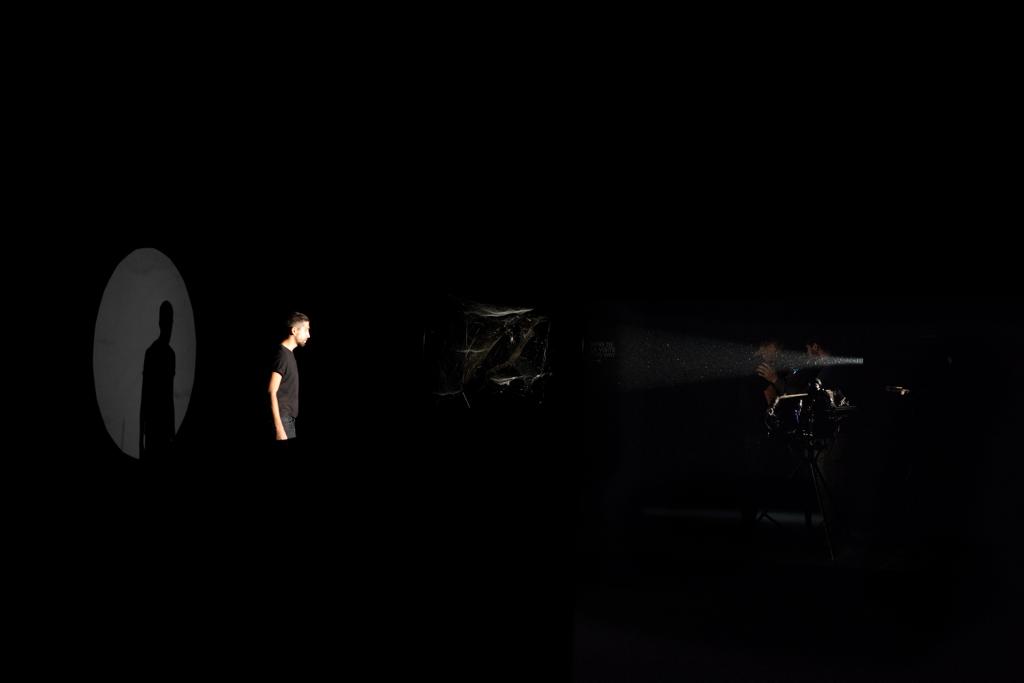

When we gaze at the stars, or [when] we observe a distant object, the Sun or Mars, these objects can disappear. You see Mars, and then eight minutes later, you realize that it’s gone, because that’s how long light takes to travel from Mars to the Earth: it also means there is always a delay. When you observe a much more distant object—for example the Magellanic Clouds—the light traveling towards us, the light that we see, left that place 163,000 years ago! This means that when we are looking at a distant object from Earth, we are always watching the past, and never the present. I decided to make a movie about this.

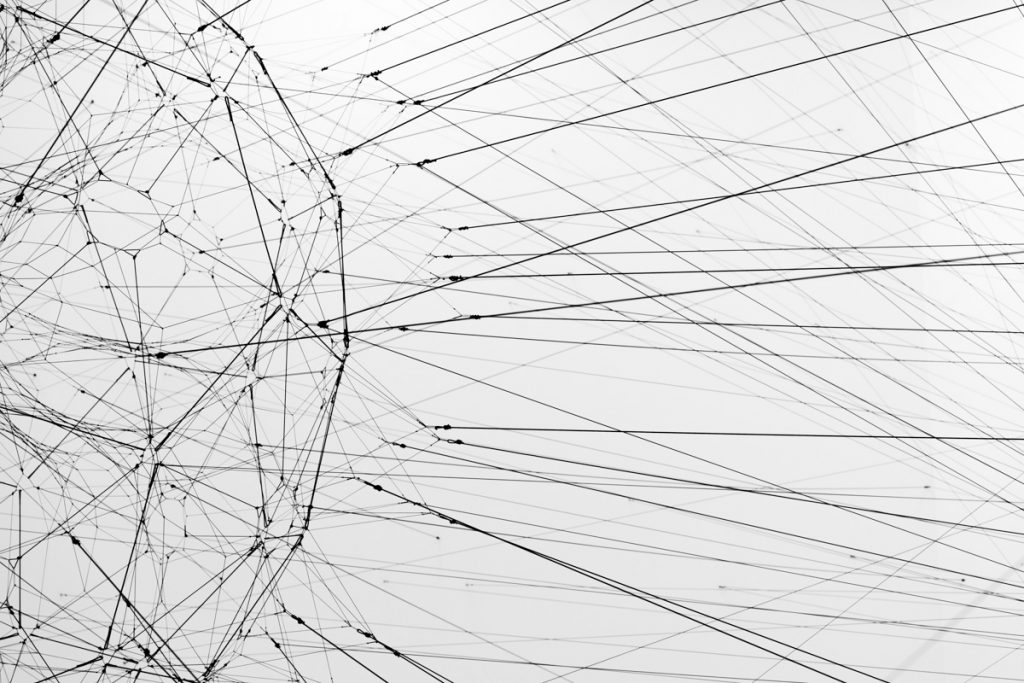

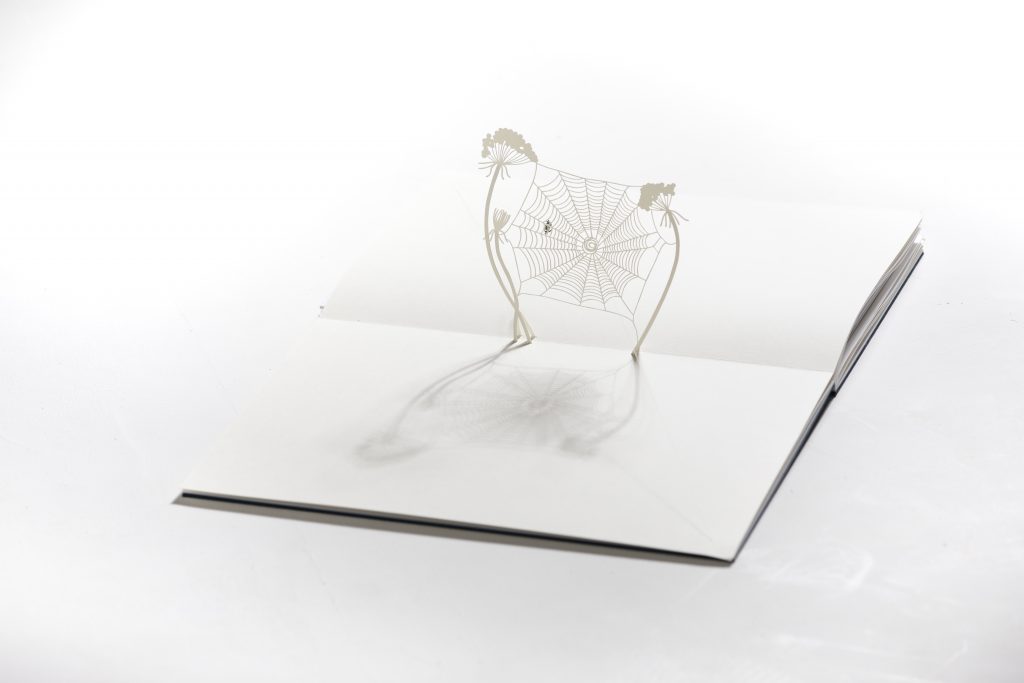

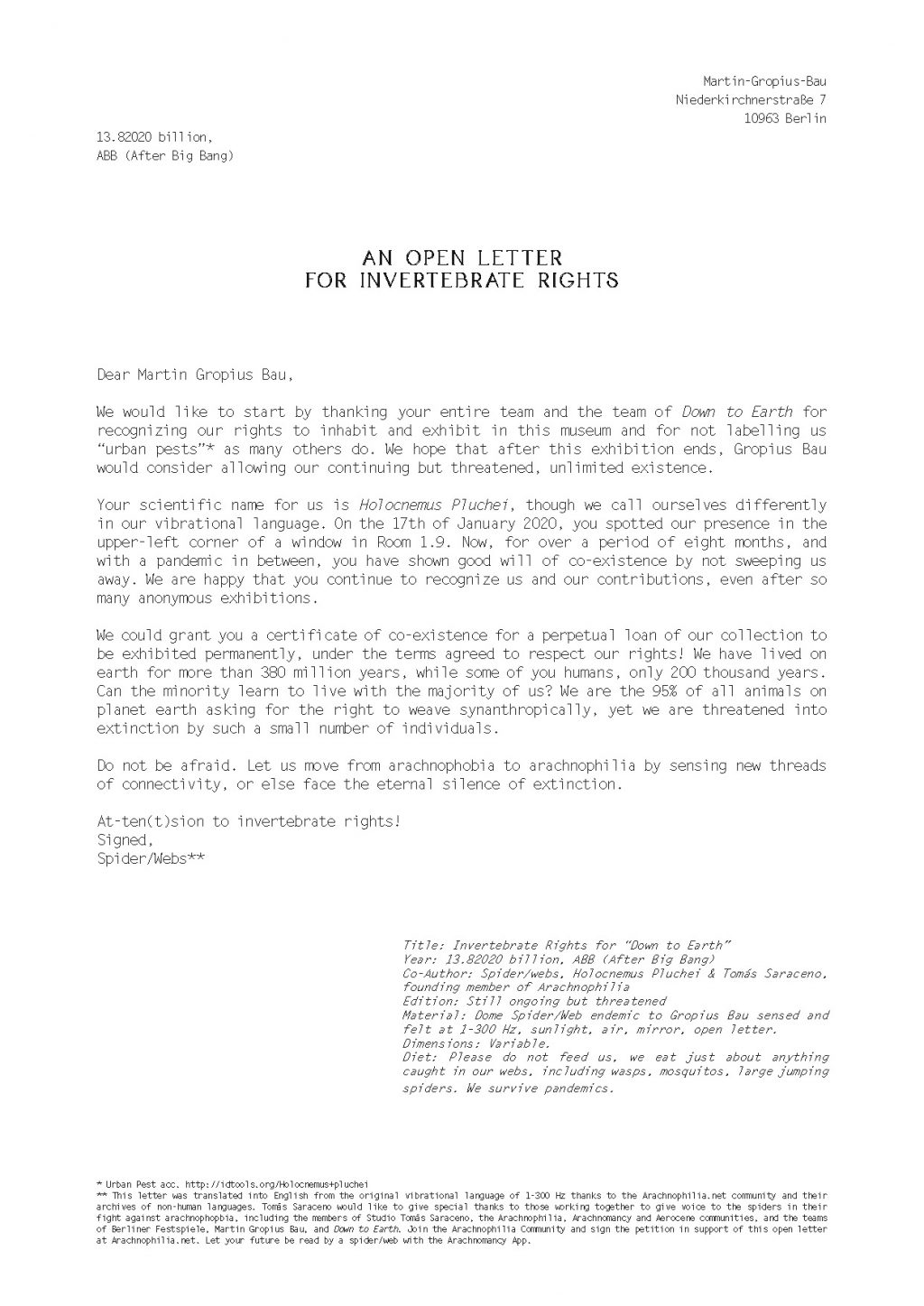

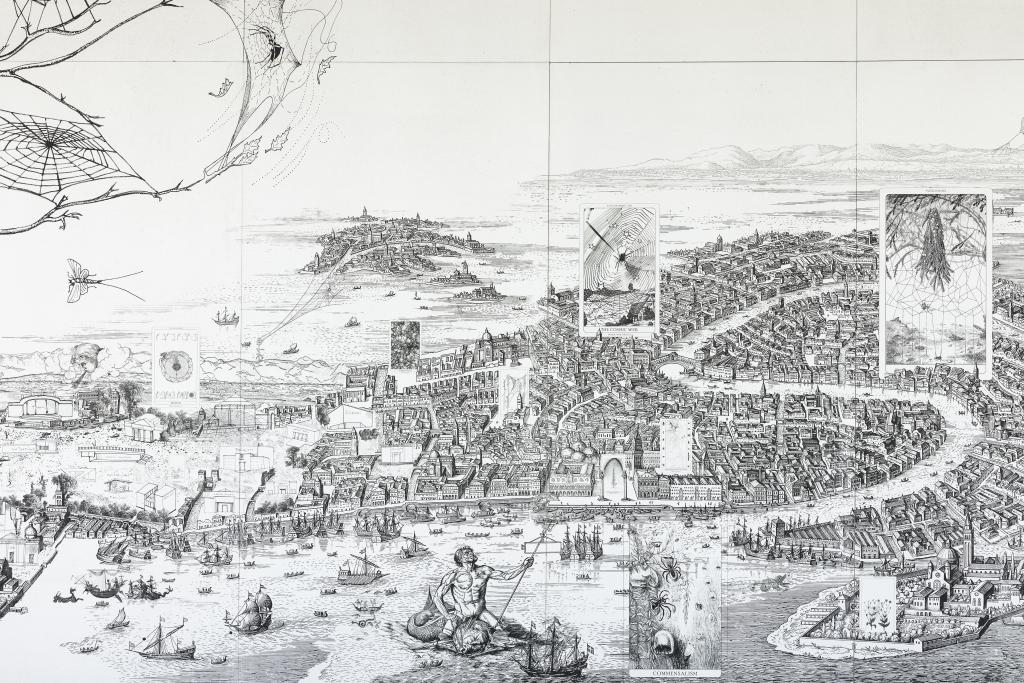

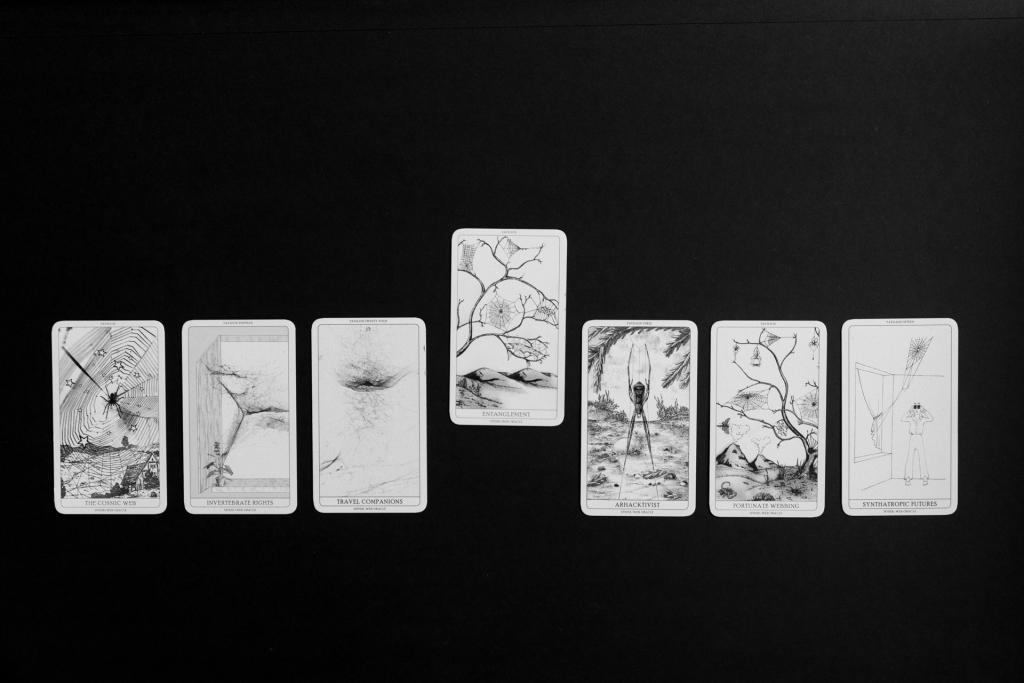

For me, watching the cosmos means being condemned to live in the past. When you make a movie, [it] is also always making the past: it’s most probably impossible to live-stream / broadcast such phenomena as formations of galaxies or collisions of black holes… I’d like to consider the idea of having a live stream of the Magellanic Clouds in real time, but once it’s filmed and projected, it becomes “the past of the past.” Photographic representation of the Magellanic Clouds takes you back 163,000 years. When you finish watching the movie, after such a long time, you can go outside, observe the sky, and after so many years, you will be able to see if the Magellanic Clouds are still there. The time of the projection of the movie overlaps with the time during which the light is traveling from these very distant objects, beyond it, back to the Magellanic Clouds… There is this very long temporality which I am trying more and more to play with: inventing a new era, a new epoch, with which I am now challenging everybody. We are talking about [the fact] that we live in the Anthropocene, the age when humans are playing a major role. A part of humanity has become a kind of geological force, stronger than any other geological force ever present on this planet. The climate has changed in many ways, and new forms of life may have appeared, as well as different ways of inhabiting this planet. In spite of this we can also speak of a new era, where human beings, or maybe spiders, are in an expanded dialogue of interspecific communication, which might spark new imaginaries of how we might live differently from how we live today. Because the way we relate to other species at the moment is not a sustainable one, nor is it an ethical one, as it often poses a vital threat to them and afflicts humanity as we know it. I have great expectations for us, but we could disappear if we don’t change certain habits. Similarly, I suddenly got the idea that spiders could become the main artists in exhibitions, rather than remaining in the background, as we constantly try to sweep them out of the gallery. Then suddenly they became the artists, and that meant we could shift responsibilities, combining or taking what was in the background and putting it in the foreground. Such shifts of temporalities and positions try to make some synesthetic experience having to do with perception. Contrary to the first work we also thought of compressing frames into a short glimpse. It fundamentally plays with the notion of time, with one’s ability to perceive something very short, lasting only a second, like a compacted ray of light, almost like a parody. It’s nearly impossible to see that amount of time, unless time were to accelerate and we could travel to another dimension. We know that our sensory perception is usually between twenty-five and thirty-five frames per second: this also gives a format for cinematic technology, and how one perceives a standard movie. There are animals that can see many more frames per second than what we humans are able to see. The work in its full extent may not be visible by humans, but it is also an invitation to other animals, other species, to see this movie: maybe bees that can see infrared colors, or dogs that are able to hear infrasound. Humans see only a small spectrum of colors, but there are many animals on this planet that can see and hear things that for us are completely alien. All these works that I do are also an invitation to other species to come to the museum and see them. My intention is to draw a more traditional museum audience — humans — into another Umwelt—what Jakob von Uexküll described as a particular environment, the unseen reality of other species.

Making a movie of this length might be taken as a kind of provocation, because one might say, “How can it be?” You can really get disturbed, because you aren’t able to see it, or able to know what will exist on the planet as we know it… It is an exercise to understand time, to reevaluate [our] current abilities to perceive, to see, to understand where we stand_

Excerpt of a conversation between Gonzalo Ortega and Tomás Saraceno on occassion of the exhibition 163, 000 Light Years at Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Monterrey in 2016. Published in 163,000 Light Years, the catalouge which acompanied the exhibition.

...