...

Silent Autumn

“[Plants] have transformed for good the face of our planet (…). It is through them and with their help that our planet produced its atmosphere and makes breath possible for the beings that cover its outer skin. The life of plants is a cosmogony in action, the constant genesis of our cosmos”—Emanuele Coccia

Source: Abbildungen Industrie- und Filmmuseum Wolfen, Bildarchiv.

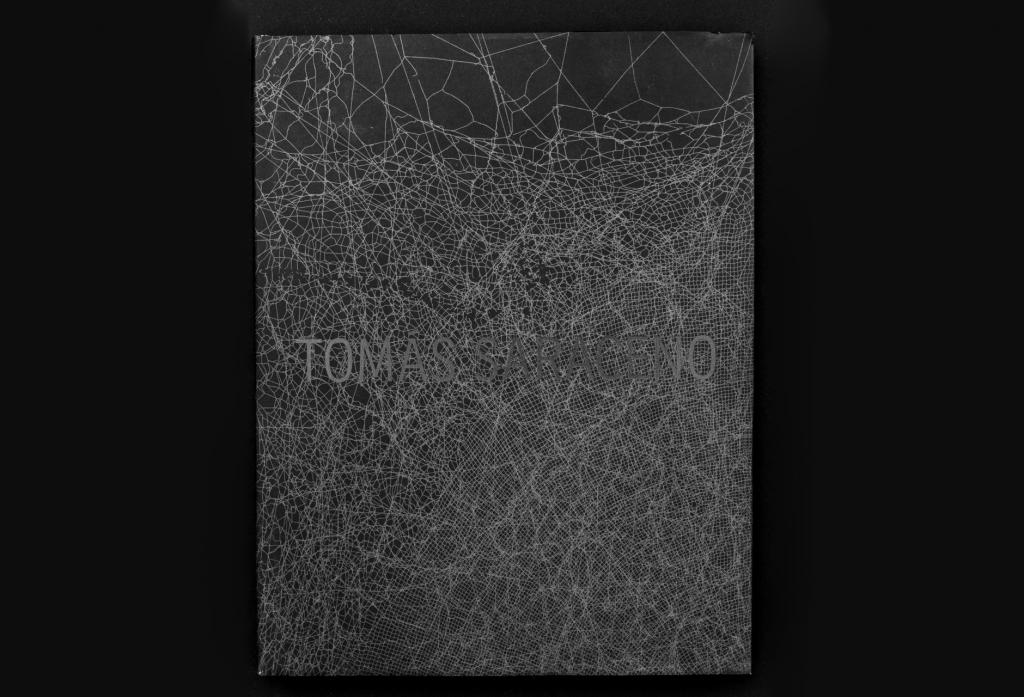

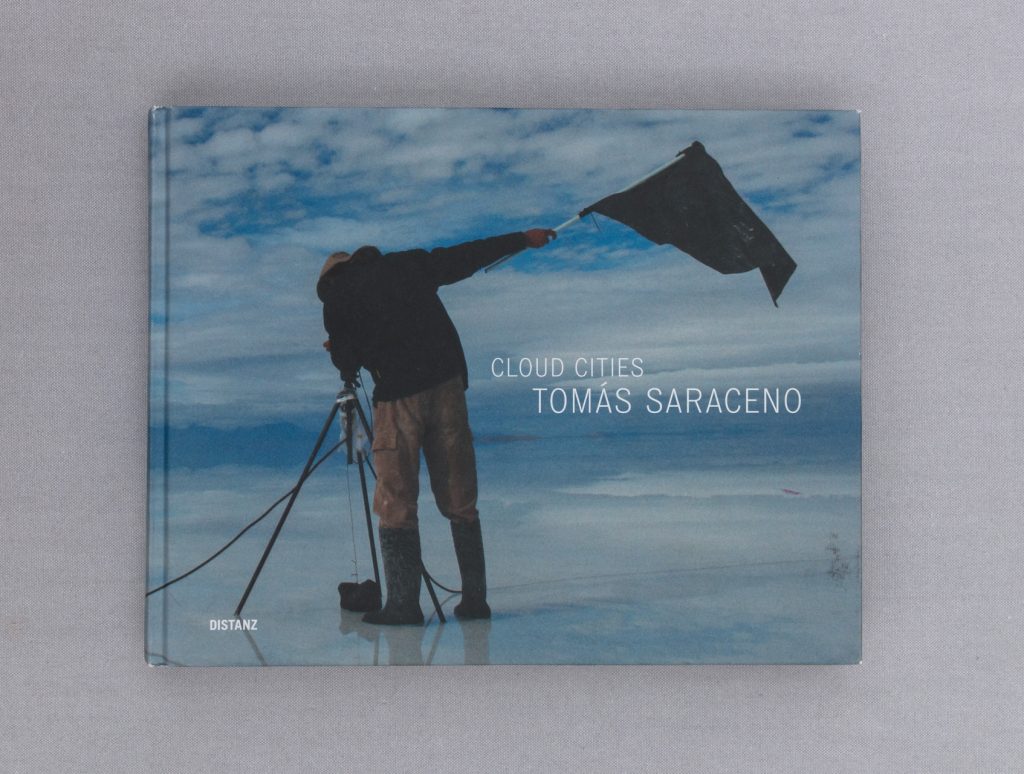

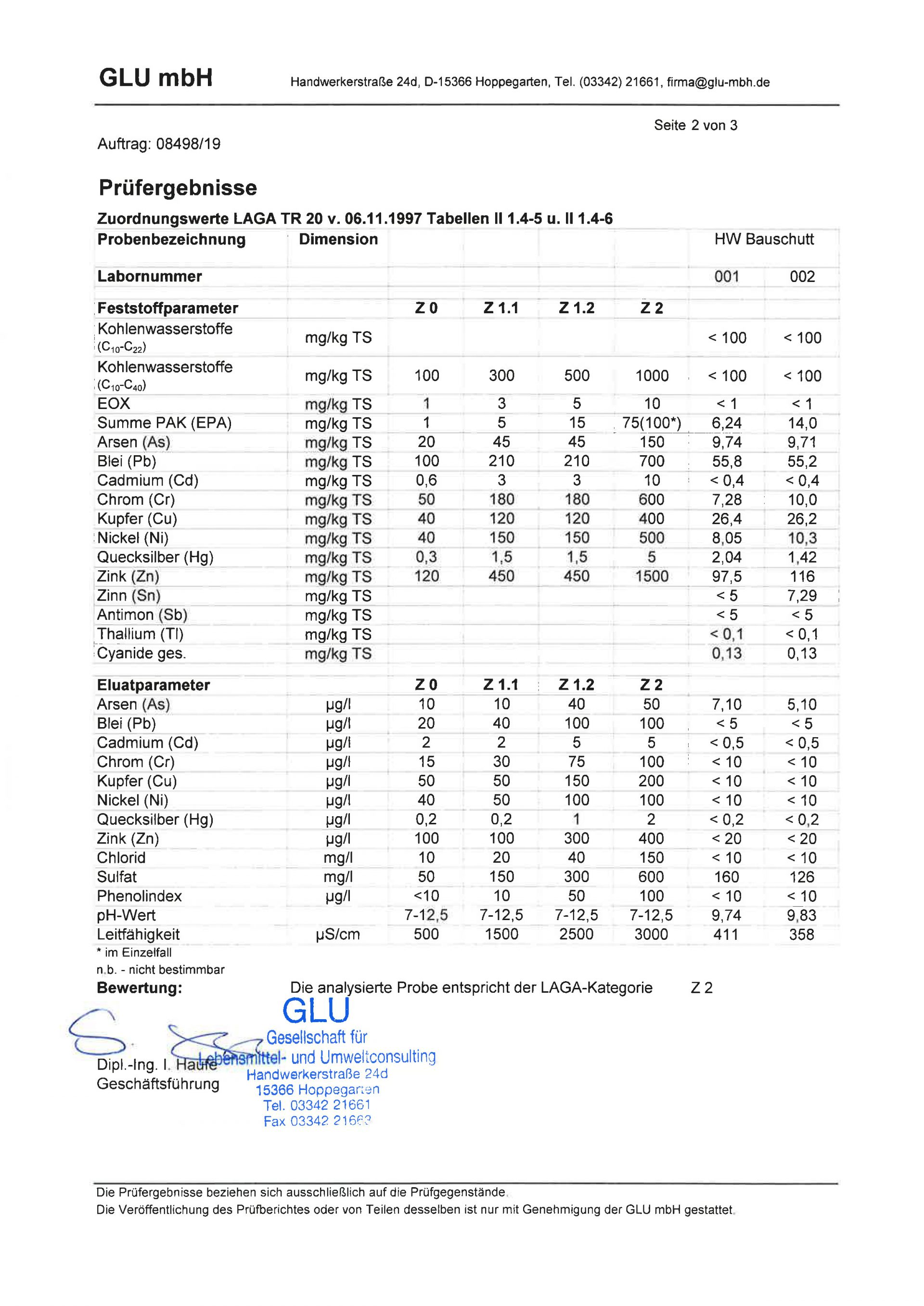

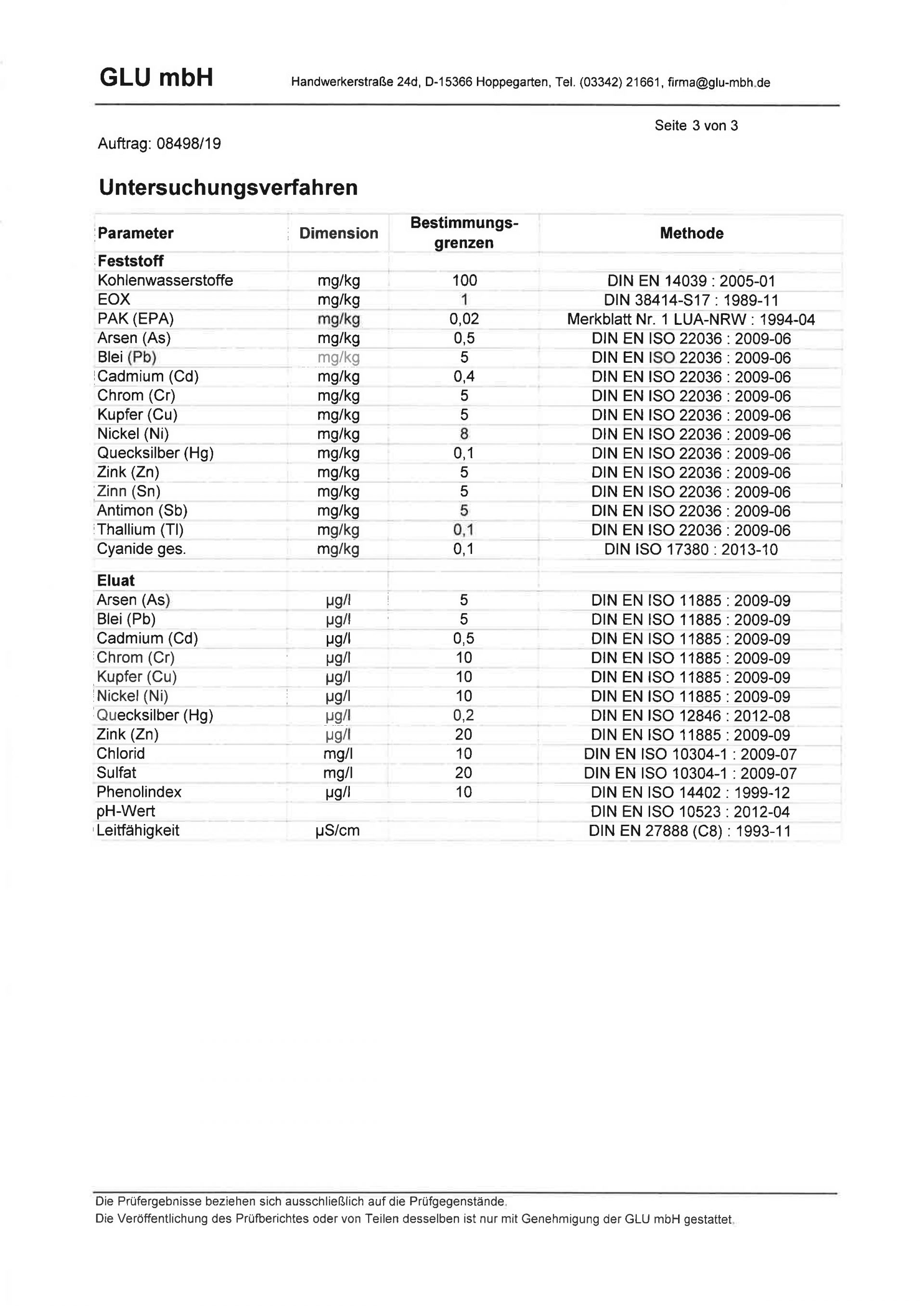

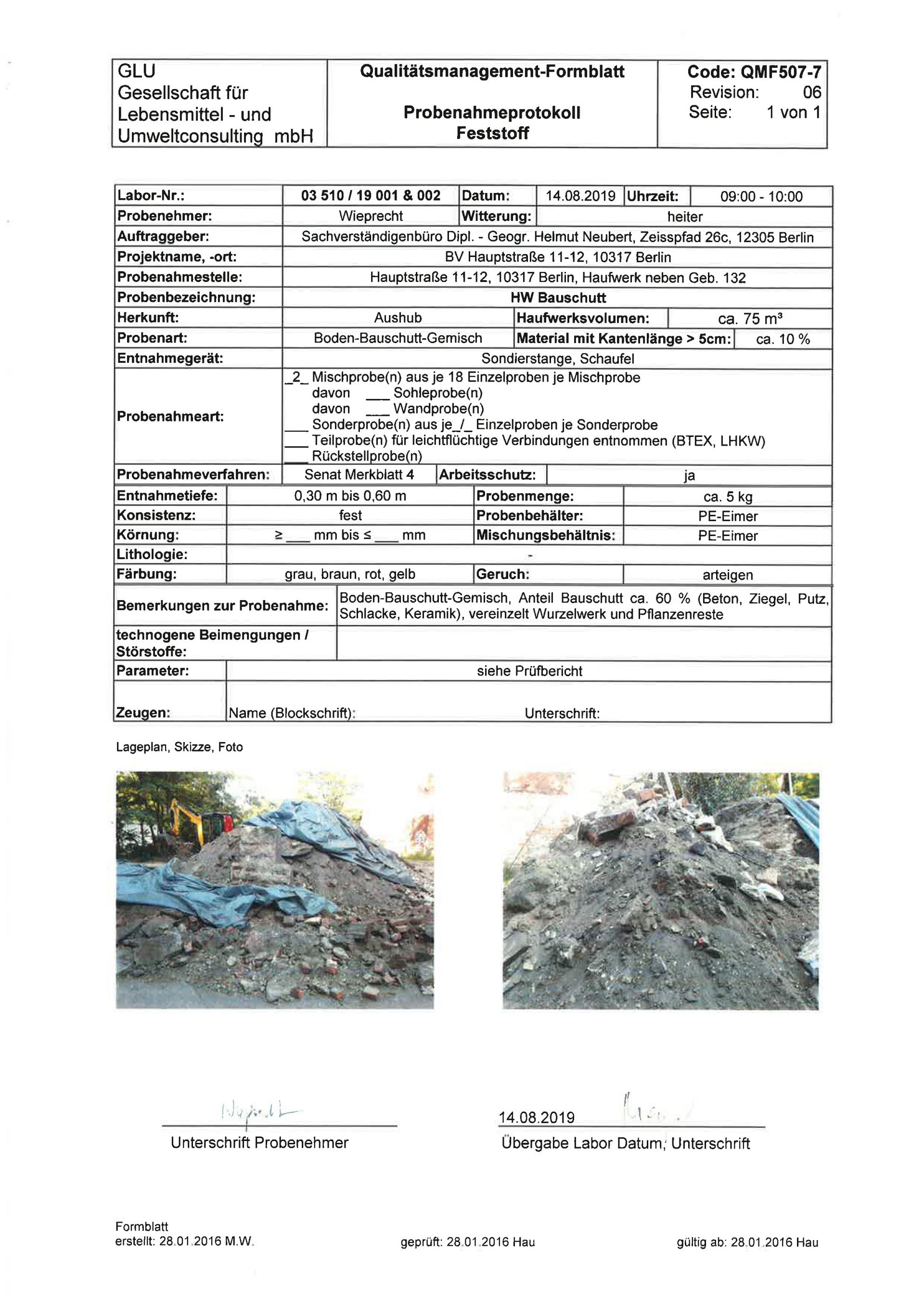

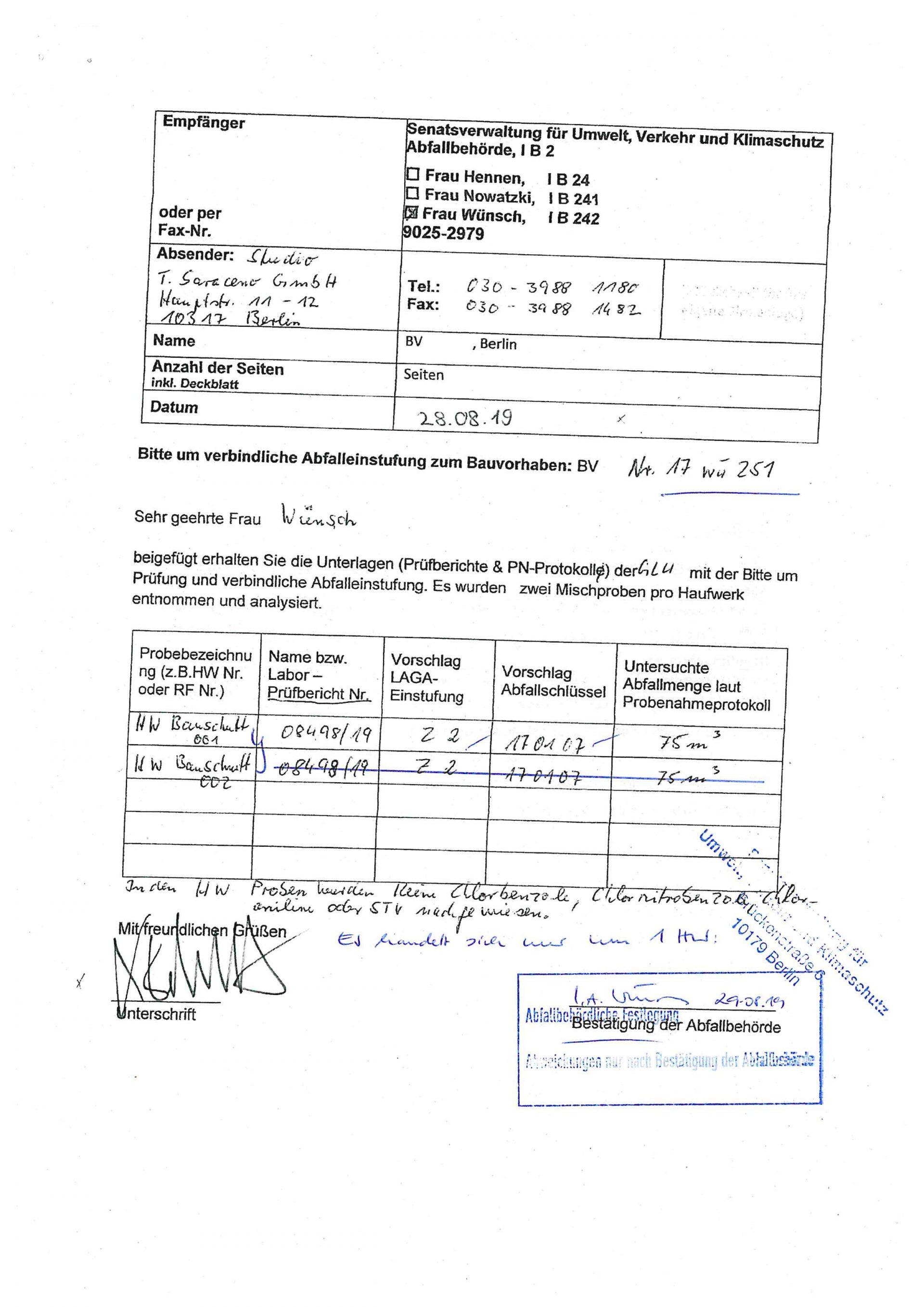

Studio Tomás Saraceno occupies the factory building on the former site of photographic film and dye manufacturer Actien-Gesellschaft für Anilin-Fabrication (AGFA), famous for its breakthroughs in the production of analogue color film photography.

Since locating to the building in 2012, the studio has grown into the space, noticing and becoming a part of its multispecies ecology. Embedded in its web of coexistence, however, is a history of chemical colonization. Until 1994, such factories in the east of Berlin would deposit their poison into the banks of the Spree. Though, the end of such activity had not come soon enough: despite the decontamination of the earth that is currently being undertaken, there are still poisoned soils below the studio today.

A history uncovered by the artist’s own locality, one revealing of waste, its geographies of disposal and the colonisation of colour, are woven into the Capitolcene’s narrative of supply and demand. Confronting society’s long-held perception of nature as a force immutable, a story is told of that which should have never grown. Companioning the delicate compositions of artwork series Silent Autumn (2021), whose composition’s colour and growth have registered the Earth’s human-made distortion through their explication from a building’s underworld, the malignant impressions left upon the land of Hauptstrasse 11-12 are uncovered. Taken as material witnesses to a contaminated earth of human-made doing, these artworks form the basis of inquiry within a new thread of the artist’s long-standing work in profiling environmental injustices, historic and present-day.

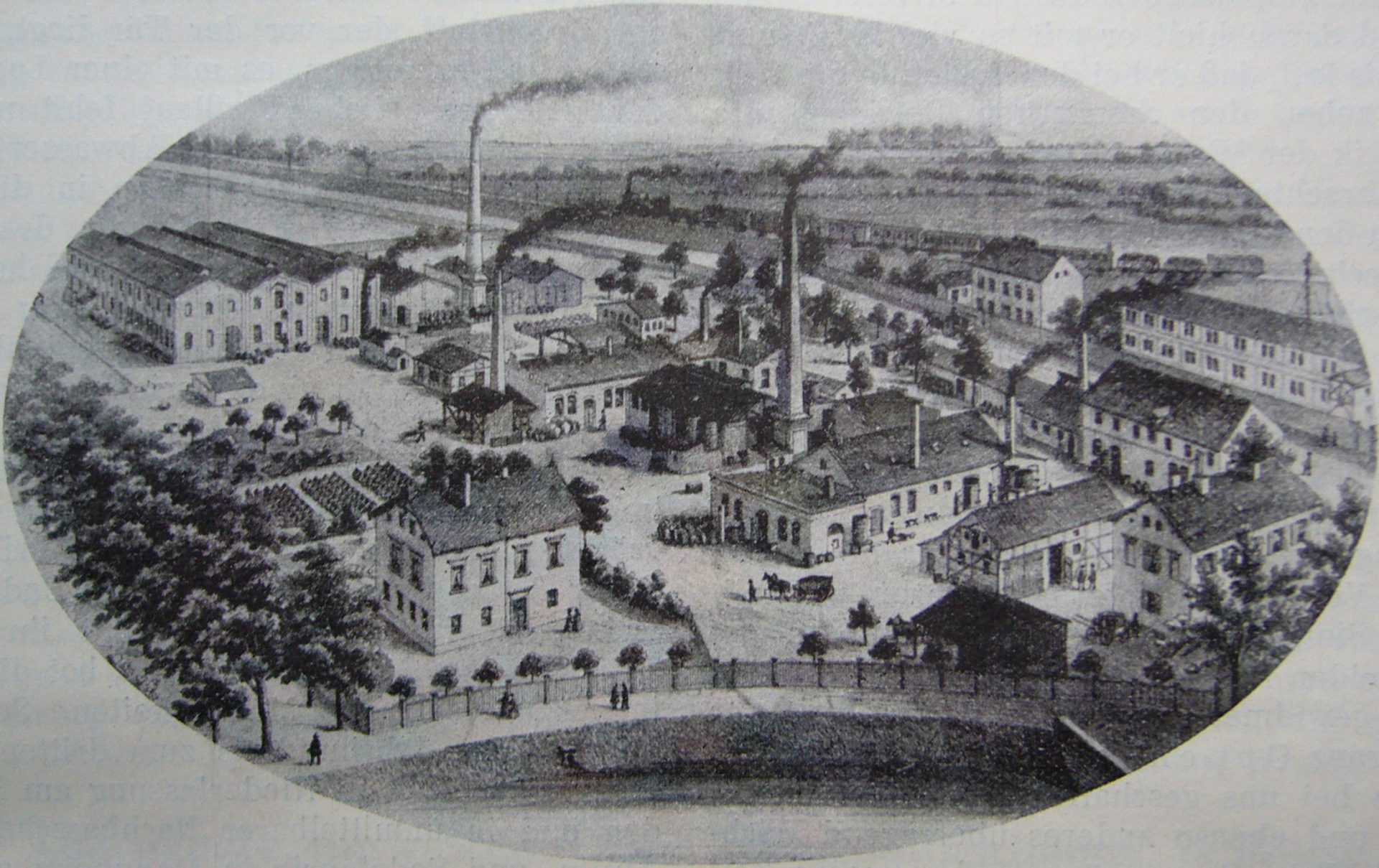

Agfa-Fabrik Rummelsburg, 1877. Source: Wikimedia, public domain

“The site, located directly on the Rummelsburg Bay in Berlin-Lichtenberg, has an industrial history of more than 100 years. Initially used as a dye works, the “AG für Anilinfabrikation” (AG for Aniline Production), later Aceta, which was absorbed into IG Farben from 1920, was established on the site, including neighbouring properties, in 1880.”

—‘History of use’, translated passage from from Polyamt Berlin

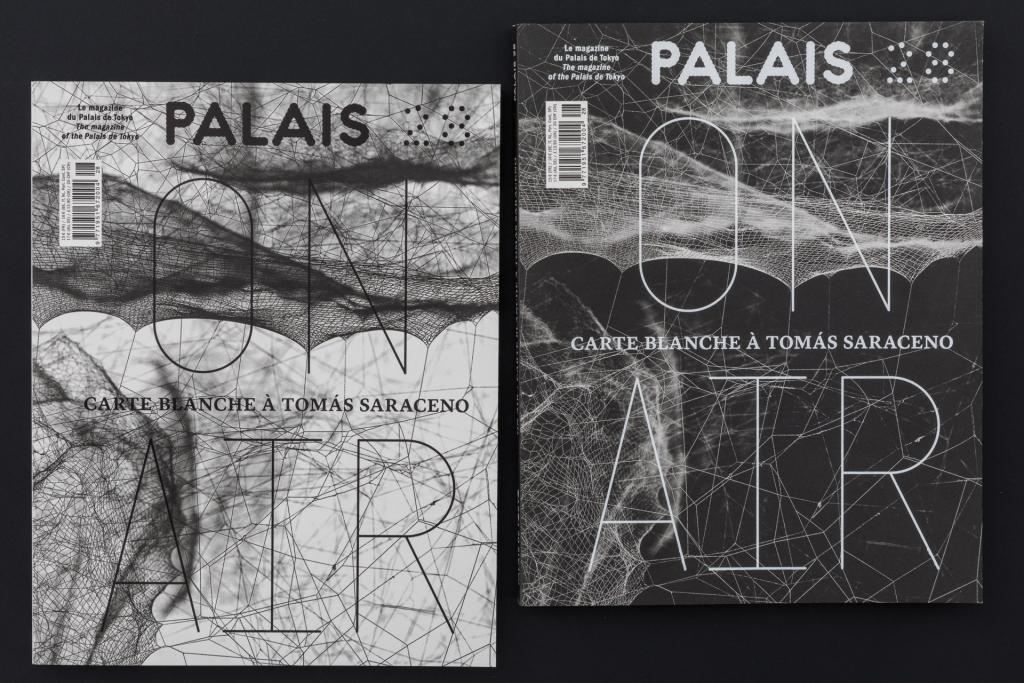

IN SEARCH OF NATURAL TRUTHS

Source: Abbildungen Industrie- und Filmmuseum Wolfen, Bildarchiv.

In its years as a manufacturer of dyestuffs, Agfa had attempted to faithfully reproduce pigments of nature, most notably in 1878 when it invented the dye Malachitgrün (Malachite green), named after the mineral of nature that bore a similarly intense hue. What would become the company’s most successful colour was used as a dye on silk, wool, leather and paper, but found further application more controversially as an antimicrobial ‘medication’ for fish in the aquaculture industry. As other pigments produced by Agfa were similarly derived, its fuchsin and gentian violet dyes had been named after flowering plants, nature was inadvertently woven into the processes of patenting and commodification of colour.

In 1883 the colour red was synthesised by Paul Böttiger, who at the time was working for the Friedrich Bayer Company in Elberfeld, Germany. His employer took no interest in a hue this bright – Böttiger sooned filed his own patent for the pigment and sold it to AGFA in Berlin. A shift from naming by nature led the company to market the pigment through an exoticised ‘Congo Red’, launched weeks after the infamous Kongokonferenz (Congo Congress) concluded in 1885:

“Since the West Africa Conference was held in Berlin, and the central issue was the Congo—an exotic locale to Europeans in 1885 and a name that was on the tip of every tongue—it is not surprising that a Berlin dye company (AGFA) gave the name Congo to a sensational new dye debuting at the very same time. The name was an effective marketing tool. AGFA filed a patent for a modification of the Congo red dye on March 17, 1885, less than a month after the conference ended; this patent application mentions that Congo red was already ‘well known.’”—David P. Steensma, “Congo” Red (2001)

Despite the wave of proceeding dyes named in similar fashion (Congo rubine, Congo corinth, brilliant Congo, Congo orange, Congo brown, and Congo blue), the earliest red pigment has fallen out of use due to its toxic, carciogenic properties evidence by the use of chemical benzidine.

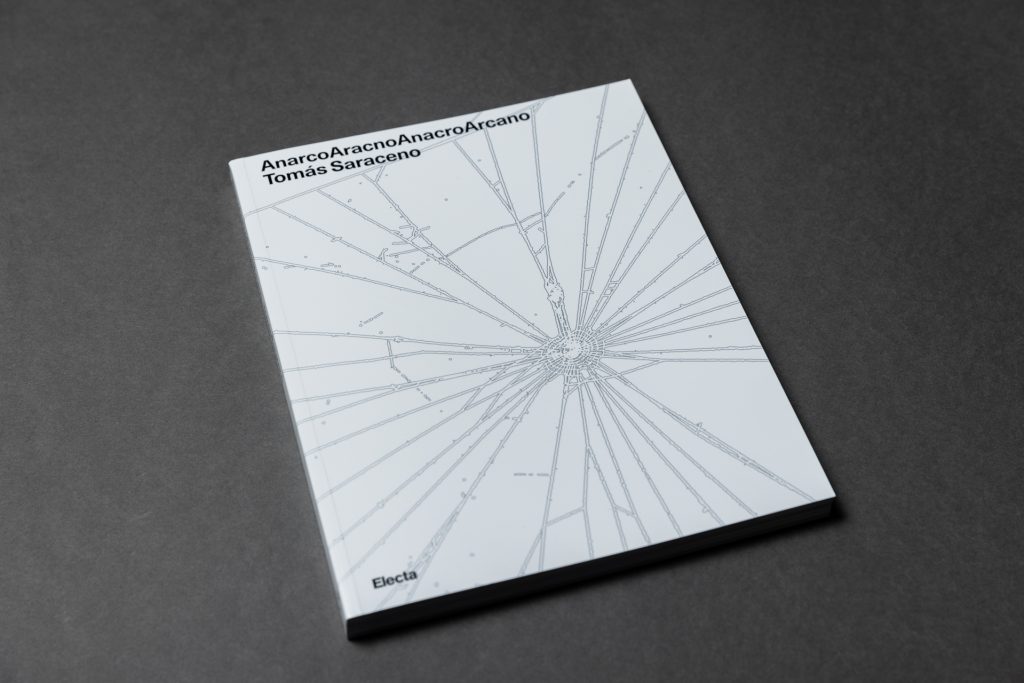

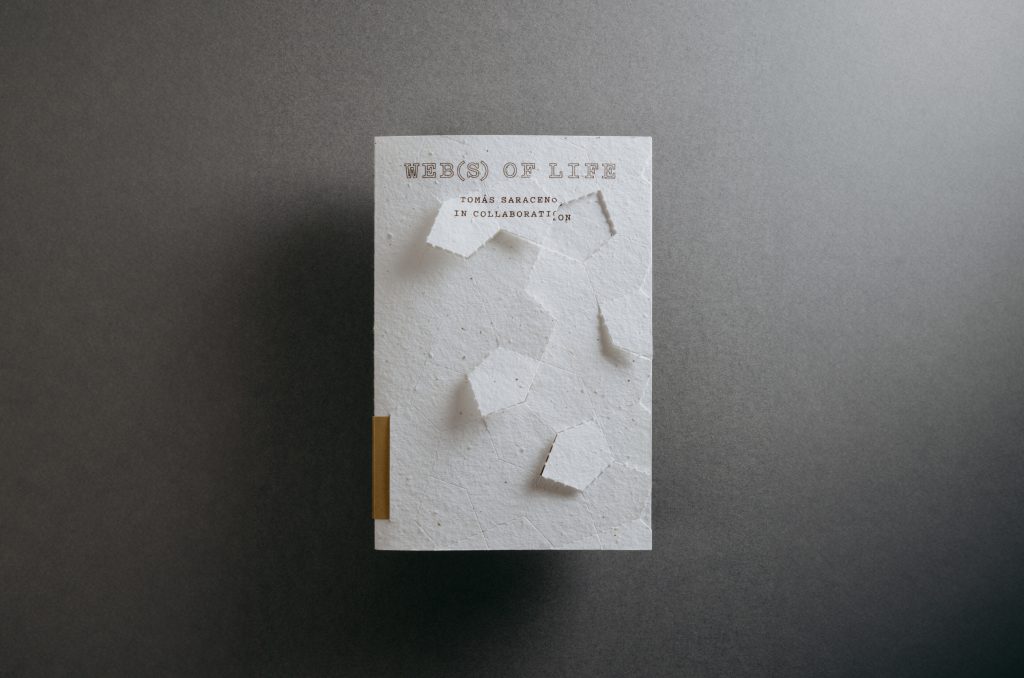

(WEBS OF) LIFE IN AGFACOLOR

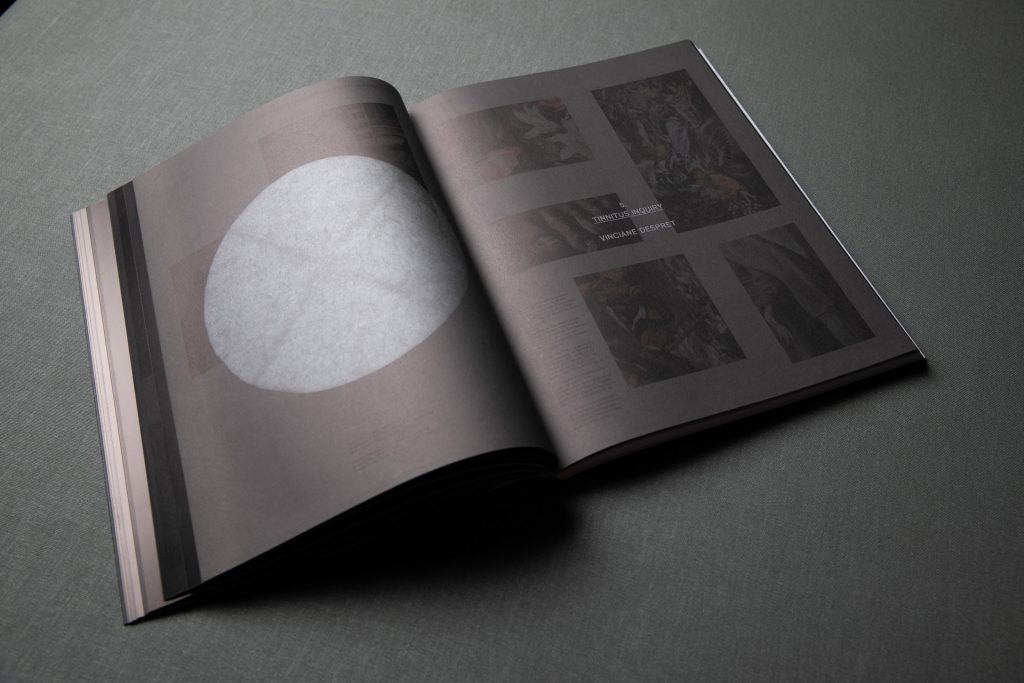

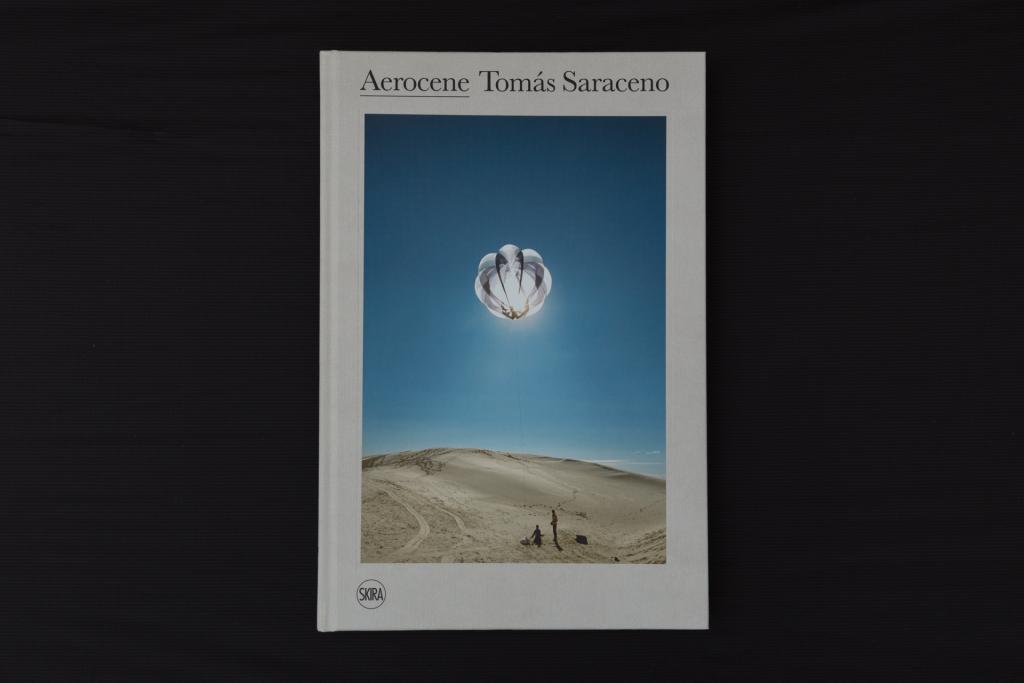

Silent Autumn (2022). Courtesy the artist, photography by Studio Tomás Saraceno.

In 1916, AGFA entered the market of photochemical products, most successfully through the production of dry plates and photographic colour film – Agfacolor. Their history as producers of the photographic process, symbolic as the exposing of light through the medium of film, is refracted critically by Tomás Saraceno today, as the foliage that composes the artworks are refigured as the direct interlocutors of light’s transformative potential. Choosing not to halt that process of exposure, the flowers will continue to ‘grow’ in their narration throughout the exhibition’s run.

Just as chemical contamination has been proven to alter the very stuff of nature from which Agfa’s color dyes were drawn, so too are earthly histories of decay illuminated in the name of mechanical reproduction. Directly adjacent to Silent Autumn (2021) is the same image reproduced: photographed on Agfa film stock and printed on Agfacolor photo paper. Here, the seemingly benign process of photographic capture is investigated and opened, exposed and analyzed, its politics and pollutants laid bare. The site of the artist’s studio pays witness to these histories of contamination, unfolding still today in the Capitalocene under the guise of the sustainable industry of lithium mining. Gesturing towards more sustainable futures, the artwork presented for a critical indictment of the processes of extractivism whose effects are redoubled upon the soil in the form of contaminated earth.

ANTHROPOGENIC LANDSCAPES

In Silent Autumn, against environmental injustices, historic and present-day, a history of waste and its geographies of disposal are woven into the Capitolocene’s narrative of supply and demand. In a globalized world where rituals and habits have transformed the earth at rhythms of genocide and extinction, where our habits of consumption have reached unbearable levels, the artwork asks: can a poetics of (im)mutability offer us a means to remedy history’s divergent quest for natural truth?

...